The Wrestlers

A poetry collection (2018) emerging from a commission from Tate Britain (2011 to 2013) further supported and presented at Kettle’s Yard (2015).

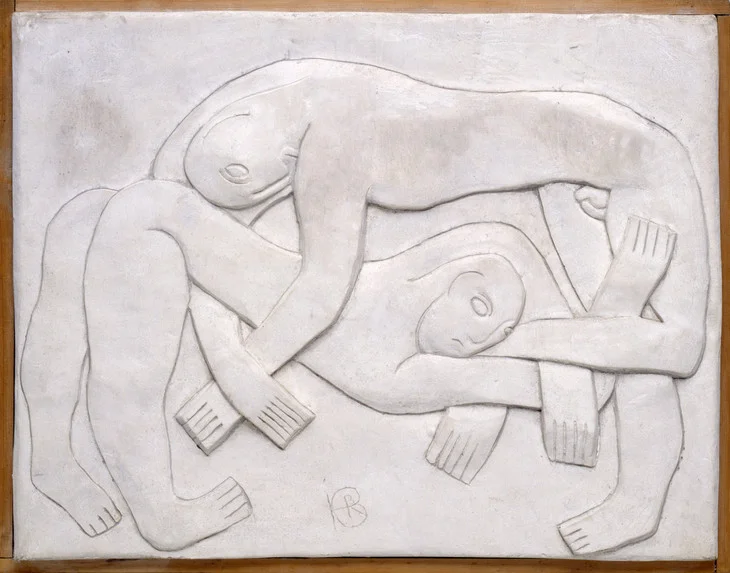

The original suite of 10 poems responding to Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s remarkable relief and it’s 9 copies served as a catalyst to explore the sport of wrestling, which I’ve practised since childhood, as a aberrant metaphor for internal conflict. You can read the poems and an article accompanying them from 2013 here https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/wrestlers-henri-gaudier-brzeska/a-poets-response

The original poems aim to evoke and subvert the modernist methodology of Gaudier-Brzeska’s peers while the poetry collection presents a more flippant and post-war European poetic aesthetic, drawing in poems written over a seven year period.

Poetry collection with Kingston University Press (2018)

78 pages - £7.99 currently out of print

From the publisher "Wrestling, the world’s oldest sport, has been used by artists, poets and sculptors as a metaphor for the internal struggle of the human mind for millennia. In the poems of SJ Fowler it becomes an action verb, a metaphorical crux which reflects not only upon the contradictions of our interior selves, but also the endless proliferation of entrenched argumentation in our contemporary world. Finding its origin in a commission from Tate Britain, where Fowler’s poetry responded to Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s extraordinary eponymous relief, The Wrestlers is an accomplished collection from one the UK’s most thought-provoking poets, often playful, surreal, satirical and ambitious."

Below you can read an extraordinary interpretation / understanding of the book by Richard Marshall, or visit it here https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/the-sacrifice-throw-sj-fowlers-the-wrestlers/

In a sense it is a book that features no actual wrestling, but through my experience with the sport (which I've come to understand as a means of navigating touch, physical space and consciousness, bodily tessellation and manipulation, and a sublimating means of conflict without death - one ubiquitous in human and animal culture) I've used the notion of the poetry collection to evoke what is most powerful and strange about wrestling as a metaphor, an action verb as the publisher has said, but also something invisible and ghostly.

A poem from the book: CHEMISTS OF SOUTH AMERICA ARE SICK OF YOUR JOKES {NERUDA TO VALLEJO} on WazoGate

Published: a poem a week Ep.33 - 'Old time wrestles New time'

August 26, 2018 - so lovely to be part of lizzy palmer and david turner to feature me in the 33rd episode of their elegant succinct podcast, a poem a week, with a poem from my newish book The Wrestlers.

For more from them visit: lunarpoetrypodcasts.com/ www.facebook.com/apoemaweekpodcast

twitter.com/apoemaweek

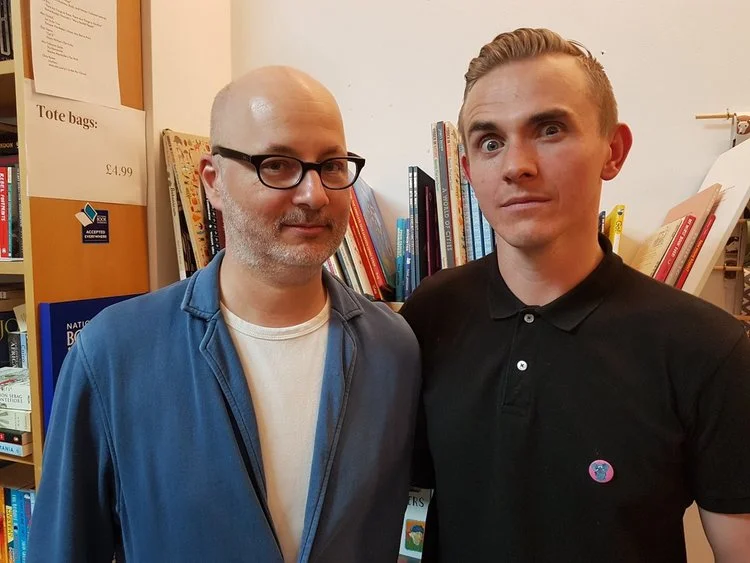

Launching The Wrestlers at Burley Fisher bookshop July 22, 2018

I had the pleasure of launching my new book on the kingsland road at the beautiful Burley Fisher bookshop this last week, alongside two friends Vahni Capildeo and Zaffar Kunial, who were also launching books. It was a lovely night, for while I always feel a little sponge when launching my own works, launches tend to be disappointing, inevitably, perhaps, on this occasion it felt more intimate, communal, relaxed. We gave some short readings and enjoyed the long summer evening in a warm and book filled corner of the city. Burley fisher is a grand place, I sincerely recommend anyone visiting the city pops in to find things that havent yet heard of, as i do, and big up to zaffar and vahni's books, both of which are brilliant. I was grateful too to so many friends who showed up in support. www.burleyfisherbooks.com/

Half launching The Wrestlers at The Oldest Sports event at Rich Mix : June 30th 2018

A strange, balmy, intimate and fun night. A chance to celebrate fight sports, something ive always been around, very passionate about, with other poets and writers who share that love. It felt very much like a disparate but unified group of artists playing with the same material, often tangential and weird, and so really beautiful for that. A wee bit quiet, being world cup and summer times, but perhaps better for that, being notably ours. Some great performances worth watching up here http://www.theenemiesproject.com/pugilistica/

I read one poem from the wrestlers here, after waffling on, which was the real performance

Wrestliana event at Burley Fisher Books May 12, 2018

I had a lovely evening in discussion with Toby Litt to marks the release of his Wrestliana book, pulled in gently as the resident writer who knows about wrestling. We chatted about lineage, melancholy, regionalism alongside the wrestling in front of an intimate audience at Burley Fisher which is a really beautiful bookshop with a deserved following on Kingsland Road. Nice to be asked to do these kind of events, talking wrestling and boxing, as they are resolutely hobbies for me now, but the first things I truly loved to do, so will always be part of me, and seem even more important and attractive now I spend most of my time doing writing things. Worth getting a copy of Toby's book here, it's really ambitious and energetic. https://www.galleybeggar.co.uk/shop-1/wrestliana

Teaching wrestling to poets as movement for Vital Signs July 25, 2018

A generous invitation given as part of The Wrestlers release and launch into the world, extending wrestling beyond a poetic metaphor for me into something like the world of dance http://www.vital-signs.org/vital-signs-wrestling-with-steven-fowler/

"Today we were delighted to welcome the prolific writer and artist Steven Fowler, whom Scott has known on the UK poetry scene for many years, having been involved in a number of the extraordinary international collaborative projects that Steven has made his name curating. Steven has the distinction of having practised wrestling since the age of three, and it was this expertise – as well as his knowledge of and commitment to poetry -- that led us to invite him to Salford. As our theme of ‘wrestling truth’ has taken hold, alongside our interest in the Biblical story of Jacob wrestling with the angel in Genesis, we felt it would be valuable to begin exploring the movement language of wrestling itself – and we were not disappointed! Steven took us on an amazing journey through a whole host of techniques including pummelling, underhooks, knee taps, single leg, rock step, shots, wrist grips, the neck tie and Russian tie and each move opened up new ‘movement worlds’, as he described them. In his notes shared with us before the session, Steven described wrestling in the following terms:

Wrestling is essentially the technical development of utilising the human body to manipulate and move another human body. It is an art predicated on using balance for balance destruction, understanding body motion and mechanics in order to nullify these things in your opponent and the development of force, motion and power generation through the body with technique.

It is the consolidating of an a priori act, a means of establishing social dominance through non-lethal combat – one prevalent in children, instinctively, and pre-dominant in the animal kingdom. It is a miniature war without death, culturally.

It is the aspect of non-lethal combat that makes wrestling highly suggestive for our developing poetics of embodied ethical critique, and we were deeply excited to be able to engage with this movement language. We can’t help but feel that it will have a decisive role in the development of our performance. Thank you Steven for all the gifts you brought us today!"

Acknowledgements for The Wrestlers - July 2018

This collection began upon invitation and it is dedicated to Sarah Victoria Turner, without whom it would not exist. Thanks also to Christopher Griffin, Jennifer Mundy and the team at Tate online and at the Tate stores. My gratitude to Jenny Powell and the team at Kettle’s Yard for further support with the project.

Poems in this collection have been previously published, in one form or another, by Gorse Magazine, Test Centre magazine, 3am magazine, The Wolf, Poems in Which, The Honest Ulsterman, The Bohemyth, Wazogate and the anthologies The Long White Thread: poems for John Berger (Smokestack Books), The Other Room 4, Millets (Zeno Press), Dear World and Everything In It (Bloodaxe Books), Hwaet: Ledbury Poetry Festival (Bloodaxe Books) and Shifting Ground (J&L Gibbons) and Poems in Which.

The sequence César Abraham Vallejo Mendoza wrestles Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto (Pablo Neruda) were commissioned by The Hay Festival : Arequipa, Peru in 2016. The poem Bob Rauschenberg wrestles Bill de Kooning was commissioned by Tate Modern for the exhibition Robert Rauschenberg in 2017. A number of the poems in this collection were created as part of The Green Infrastructure – a residency with landscape architects J&L Gibbons. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s The Wrestlers were commissioned by Tate Britain and published by Tate Online in 2012.

A note on: Richard Marshall's epic review of The Wrestlers July 15, 2018

https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/the-sacrifice-throw-sj-fowlers-the-wrestlers/

the sacrifice throw: sj fowler’s the wrestlers By Richard Marshall. - - - S.J. Fowler, The Wrestlers, KU Press

Poetry was born at a very young age, just like me. But there’s a very old consciousness here, one wanting to create his own metaphor for poetry. Torn between realism, wanting to reproduce things as they are – the conversations, asides, fragmentary sights, because they’re strong and necessary as metaphors – and invention, via dislocation or substitution of materials or shape, or contrasts which by themselves take the object as it were away from both itself and the originals, there’s a sense of pushing and pulling both ways from all directions. And everything tends towards yielding materials that are being pushed around like this, and pulled, which are the very strong subjectivities in play but also a subjectivity you and I can have and share in, so this is push and pull, or fancy dialectics where ‘being clever is not armour’, as Fowler has it early on, where his ‘… hill of necessity turns to taste’, shows ‘taste’ as just this, you fighting with your other selves, or something like that. Sometimes nothing intrudes on other people’s rearrangements, making substitutions metaphors and nothing something. It’s all wrestling.

And in wrestling we’re conscious of rigid objects falling apart. The whole solid thing – perhaps we’re meant to think of this as society or culture or maybe just poetry or art or more likely just ourselves – it’s grasped as a sense of eerie collapse and sublime disintegration, something that we won’t be able to catch with just words printed out. And then the idea of putting that idea up in print and wondering whether we can actually have a sense of what it all meant. To do that. That too becomes wrestling.

Language has a habit – or maybe it’s its very nature – of reverberating back to its original image or sense, yielding a prejudice towards naturalism that is inevitable. This is where poetry disappears and you see the original, and then remember or experience the tension between the original and this, whatever we’re reading or hearing, and the poetry reappears. It’s very realistic, you can imagine it as a certain language, as English. As being spoken or rubbed. Fowler shows us this, a thisthat’s been imagined in this state of high degree. Rilke was able to identify with the tree. Suzuki with a pencil. Cage with sounds, rocks, plants and people. Fowler with wrestling and poetry. Or better, one as the other, and vice versa.

Fowler’s interested in permutations and parts so that the shape, size and mannerisms – especially of the bodies, that’s what’s intriguing him. How the wrestlers in the relief can be taken from different angles and overlapping interests, and none of the things have a central point or vanishing point or any point even, obviously, but might be put one inside the other like Russian dolls, wondering what we might anticipate and what might result, or has already resulted. Fowler has a real interest in this, like it’s an interface with the soul, a ready-made, a proletarian quality that belies any suggestion that the more money you have the more abstraction can be laid on you. Here the degradation that is luxury isn’t the point. This is an art as mythology, as sexuality and as morality. But mainly it’s desire.

So the poems work with everything and everything we’re left to say afterwards is just to say whether we get a sense of life from them or not. That has to be what can’t be avoided, to ask not whether they’re contained somewhere somehow in our lives but rather, do they settle our lives? What gives them life is ‘life’ not the process of understanding the process, nor the poet working out of her skin to accomplish certain things. But the poems are by-products of an activity and Fowler is remarkable in his ability to understand that, delineate it and have them settle with life, real and expansive and rich. The wrestlers are perfect for him – he takes them so lightly because he’s so serious about them – wrestling that is, not so much the actual art work he’s pivoting off – and so there’s his ability to make the tension work in terms of the subject matter – the repeated tropes of wrestling and wrestling with and wrestling between and so on. Its not myth, or morality driving him though but it is desire. What this does is eliminate composition, form, arrangement, relationship, figure, well, not really, but you see what I mean; there is just this thing he wants to get hold of, stick it at the centre of the page, like an account of an anatomy, of a fight, of a gesture, of a position and not get distracted, flustered or even wonder whether or not that’s a great idea to do or not. Because when the hell did we rely on artists of any stripe to have a great idea? We don’t need their ideas – and Fowler gets this – we need their art. And Fowler here is fresh with desire for the Gaudier-Brzeska but he’s not spooling out ideas. What we’re getting is his desire to be inside and outside the work, happy to be alive now not anywhere else, not in ideas, not in showing us omens and philosophy and theory but, well, just being here in poetry. Or whatever bits of poetry might be left over after. Or to come.

The Gaudier-Brzeska is a relief, works its own plane, and Fowler’s matching it with a poetic plane, as mysterious and complex a thing as you can imagine. What can at times be frustrating and necessary and puzzling is this metaphysical plane, and what to do or what happens when its not quite maintained or it gets eliminated for a while, even for a moment, that’s what we’re getting when we face the relief and the poems. The plane gives a sense of resistance for the art, or else you vanish into meaning, clarity – and that’s the end of the business. Fowler works to maintain the plane so we can’t fall into that clarity, that finished, revealed meaning. And of course in doing so, in emphasizing the plane, there’s always the danger that you renounce the depth. That’s the other thing. Always this tension between surface and depth. The wrestling match going on, it’s between these. You see it in the frieze, the same contest. It’s what you see in David Caspar Friederich. The same play off between the skin of the canvas and the depth. It has to do with dreams about painting, dreams about poems, dreams about dreams really.

You listen to people telling stories when you’re not hearing them hearing themselves telling you. It’s at that point of freedom that you get the kind of freedom you’re looking for in the poet – its freedom weighed down with a lot of baggage. It’s the fascination of a torso wrestling the weight of an equal torso and seeing what gives. Let’s see a few rounds at least. It’s the opposite freedom of spontaneity, of imagination that just flies off. It can be joyful or tragic, no guessing which at the start, its compounded of so many elements, and really, you don’t want to think too much about it. You’re rather propelled into a kind of maniacal concentration and the real problem is then to work out how to keep that level of concentration going. You know the issue: how does the artist maintain that sort of pressured feeling and making over vast time? No doubt it’s too hard for us and is why modern stuff is so fragmentary and unsustained. Some days who doesn’t dream of Poussin, Mondrian, Pound, Dante, Beethoven, Joyce all pelagic, over warm tropical waters from inshore to offshore, flying over dolphins and yellowfin tuna, nesting on San Benedicto in burrows dug in compacted ash, calling with eerie, drawn-out, rising and falling wailing moans, in series of two or three, flying typically unhurried with shallow and easy wingbeats, interspersed with buoyant glides, skittering on the vast waters, skittering on the surface, rarely if ever completely submerged, gull artists taking years.

The blurb collects it all up. “Wrestling, the world’s oldest sport, has been used by artists, poets and sculptors as a metaphor for the internal struggle of the human mind for millennia. In the poems of SJ Fowler it becomes an action verb, a metaphorical crux which reflects not only upon the contradictions of our interior selves, but also the endless proliferation of entrenched argumentation in our contemporary world. Finding its origin in a commission from Tate Britain, where Fowler’s poetry responded to Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s extraordinary eponymous relief, The Wrestlers is an accomplished collection from one the UK’s most thought-provoking poets, often playful, surreal, satirical and ambitious.’

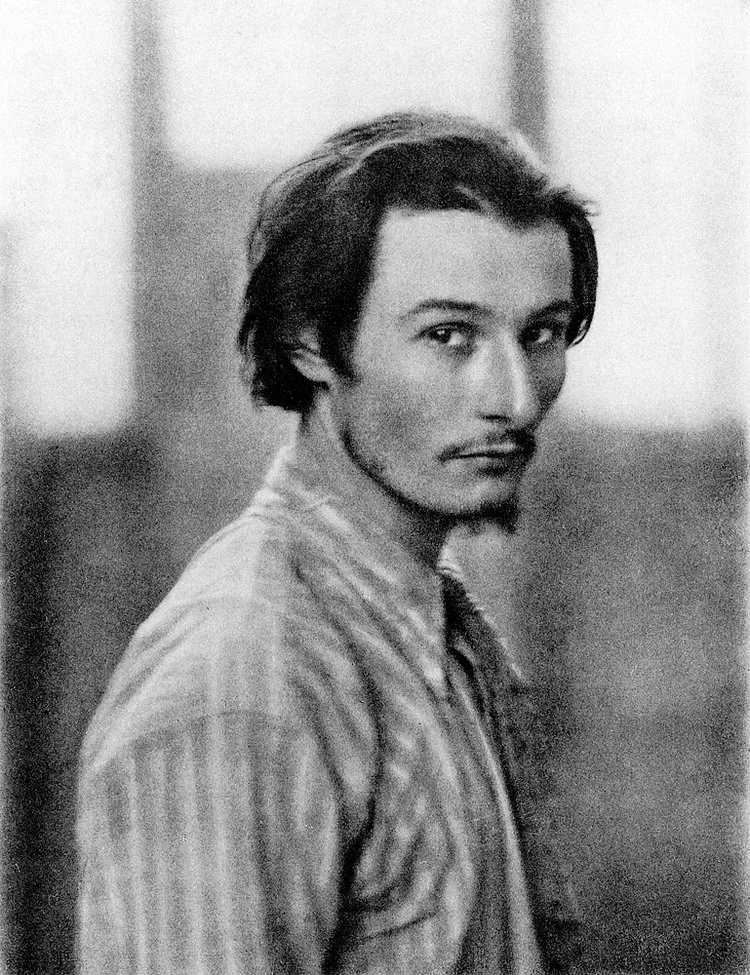

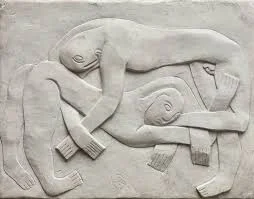

The Tate elaborates: ‘The large plaster relief Wrestlers was made in London by the French artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915) at a time when he was forging a reputation as one of the most radical and innovative sculptors of his generation. Gaudier-Brzeska was killed fighting in the First World War, and his achievements slipped from view in subsequent decades. In the mid-1960s, however, curator Jim Ede had the relief cast in an edition of nine to help make Gaudier-Brzeska’s work better known, and he gave a cast to Tate. This project explores the circumstances of the making of the relief and the posthumous cast, and asks new questions about representations of sport and physicality in modern art and poetry at the beginning of the twentieth century’.

Wrestlers and poets must be permitted and forced to steer. A wrestler/poet is a person out of her own direction. There’s a mix of passionate control and unreasonable severity. There’s a desired end but something kept off by supposed, supposing invaded, invading authority. At times the wrestler/poet sits, ‘squat like a toad, close to the ear of Eve’, at others she ‘stalks with fiery glare’, now the Miltonic lion supplanting – or supplementing, the toadish. All through there’s a ‘communicative temper’, better than ‘knowledge, civilitie, yea religion.’ The wrestler/poet struggles against the ‘huge quaggy carcass’ of unjust rule, seeks to spring the trap in history in the face of lies, secrecy and the official manipulation of truth. The wrestler is a free Commonwealth creature – again the Miltonic allusion persists – just as Richardson in his ‘Clarissa’ is nothing but a devout Puritan ruling out monarchical – tyrannical- options – Henry VIII the ‘tyrant Tudor’, Rochester, Jacobite Thomas Wharton, Bolinbroke – and a warning: ‘Beware, Peru, beware of your Peru/Beware the healthy/beware the hapless victim/beware the three denials/ beware the skulls with tibias/ and of tibias without skulls..’ which in the rude mouth of Fowler’s new collection is the ‘iron glaive’ of, oppositional, dissenting poetry living with Rousseau’s intent ‘to overturn the French Monarchy by the force of style.’ By which we mean: Fowler wrestles dissent into poetry – roundhead wrestling cavalier – erasing easy meanings, and clear sense of self.

Fowler takes his dashing poetic style to the verge of flat prose but never falls over. It’s a reversal of Hazlitt’s reflection on the prose style of Burke. Recall: ‘Burke’s style is airy, flighty, adventurous but it never loses sight of the subject; nay, is always in contact with, and derives its increased or varying impulse from it. It may be said to pass yawnng gulfs ‘on the unstedfast footing of a spear’: still it has an actual resting-place and tangible support under it – it is not suspended on nothing.’ Fowler is on the brink from the other side of this equation: his poetry hangs suspended like the bird on nothing – which is breath and poetry – but hovers at times so close to prose it grazes the ground’s intricate ways, and almost becomes something.

[The wrestlers, George Benjamin Luks]

In ‘The wrestlers wrestle George Benjamin Luks’ he writes:

‘ Criticised for his poor handling of the human anatomy, Luks answered his detractors by rendering this complex scene of two nude wrestlers. The artist’s perspective was radical for the time.

Luks’ composition effectively presses the viewer to the edge of the wrestling pit, thereby emphasizing the down-at-heel setting.

The jarring vantage point also evokes the sweaty underbelly of modern urban life, a theme for which he and fellow members of the Ashcan School would become known. Luks’s scene of entangled human flesh under duress is reminiscent.’

Here is the self-wrestling moment – this new collection is full of them -where there’s a dare being enacted, a hair’s breadth in talent that’ll make all the difference, where in that last line ‘Luk’s scene of entangled human flesh under duress is reminiscent’ is itself the bearer of all the duress, the sound poet screaming from overhead and pressing down nothing, and where the huge dumb heap of prose matter that seems to end in vanity, littleness jarring, is called out and up with those very last four syllables, ‘reminiscent’, minding us of the mind ‘hovering over mysteries deeper than the abyss at our feet; its speculations soar to a height beyond the visible forms it sees around it,’ to continue to mine Hazlitt’s steer point. We will not be told what it is reminiscent of. The allusive imagination of Fowler is constantly finding the mysteries overhead whilst he keeps his ear to the ground, close enough to sometimes threaten to tumble into the worthy, heavy immovable rocks. This is the drama of this collection, its working a way through allusions and mediation, breaking open various material things to find in each yawning gulf the imagainative life living palpy and juiced up inside it. He’s a writer who reckons that the power of the mind is as dangerous as any gun. We are left with the strange aura of an uncanny mystery that the more we peer into it becomes more like a cloudy mirror.

‘ This the best one can hope for./Ringing alps with tape, as though they were city squares./The hearts of geologists as purple lumps, but at least pumping, something arises to the surface…’ he writes in ‘The alpine wrestles orogeny’ which ends ‘ This is the place where Lazarus dug.’ Again we’re in Hazlitt territory, and with it the compounding resonance of the republican resurrectionist Revolutionary moment in Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’; ‘ The sounding cataract/ haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,/The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood’ – the rock an image of the guillotine, the mountain Montagne, the Jacobins in the National Assembly, as Tom Paulin taught us all some time ago. In Fowler the moral grossness of our days is imagined still gross but with the imagination able to rescue, despite everything, long-cherished dreams of the imagination on the senses where ‘something arises to the surface’. Fowler is resisting the dire and the dismal, the constant assault on imagination, hope and dream, the drear sensual Lockean epistemology that limits us to whatever we can see now. Poetry here is a never ending mind wrestling with dead rubbish. It contains both despair and hope, and ourselves whatever haunts us.

Fowlers’ imagination makes it possible to offer small things – oh, so many small things, and beauties –

‘ a blood red bird of the female representation on television… /Let’s hope there’s no need for dental records, antibiotics, antipathy./Let’s hope no broken bones from the eye down, looking away from the time soured,/Unable to recall the second name across the last broad century/ as dark as a heart is sensitive. Such a busy time.’

Such busy time sets up the contrast – it runs right through this collection – between the sense impressions out in the streets, on tv, in our black mirrors, in bed etc where intellect is unseen and then those great, central, visionary moments where the intellect becomes visible and the imagination active or reactivated, Lazarus- like . Hazlitt made the same contrast when he writes about entering Rouen cathedral. He sets the sublime mind, the lived, active, juiced up imagination, against any kind of empirical enquiry. Fowler’s poetry reminds us of the possibilities of what we might dare to imagine if we can unhook ourselves from the pressing realities of cabined, cribbed and walled in realities. The poet mind of the poet – the wrestler – is immortal, radical, critical and dissenting. It’s bell against chairs. But the wrestler sets one against the other, sets all against all, in order to squeeze the juice of sublime and sublimical vision. ‘Rock comes to market/but plaster comes to town./’ from ‘Relief VIII’ throws this in, and we get what excites Fowler in the next poem where he writes ‘… abandoned/ to fighting/free/is wrestling/ripped without formal training/a filthy mock clawing/biteless, eyeful, throwing rolling/staining green/no broken collar bone/no of the mind, & death/he would have/like a brick falling…/

This is spirit and buoyancy, flesh and soul, small things capable of holding the vitality of the radical dissenting imagination, the restlessness of life looking to love life and towering over injustice and tyranny even as freedom, love and justice seem hardly anything real at all. Poetry here is a ‘Leg to try’. It’s a warning against superficial motion. It’s an attempt to find harmonious, flowing, varied stalemate. It’s a ‘Shot of below’. It’s a ‘Sacrifice throw.’ What’s that? Well, he explains it best it can be as a first go – ‘ drag into a void the vacuum of overeager forward motion.’ The gusto and energy press-stops any poetic prettiness or skill, blunts any chaotic sensationalisms but at the same time opens up against any sense of solidity, wooden, matter of factness that might be a faux comparison. And baulks against ideological posturing too, slogans and unearned crowd pleasers. Fowler is a muscular advocate against stolid matter-of-factness, against propaganda and realism that inspects material qualities, inertness, impenetrability and finds them everything. The wrestler puts into motion a labour against such opposing weight, against a kind of English dour imagination that, as Hazlitt cunningly put it, does not ‘… care about the colour, taste, smell, the sense of luxury or pleasure: – [but] require the heavy, hard and tangible only, something for them to grapple with and resist, to try their strength and their unimpressibility upon. They do not like to smell a rose, or to taste of made-dishes, or to listen to soft music, or to look at fine pictures, or to make or hear fine speeches, or to enjoy themselves or amuse others; but they will knock down any man who tells them so, and their sole delight is to be as uncomfortable and disagreeable as possible.’

This version of the dry spirit , the philistine prejudice, is what requires Fowler’s push from the other direction. His wrestlers account for the fight, the complex locking together in the poet of the poet and the philistine. The series of epiphanic moments in much of Fowler’s performance gives us the jutty texture of the constant fight, the tenacious momentum determined to stop us all being turned to stone. How? By ‘Always finishing, always driving, always finding an angle.’ That’s what the poetry is for. It’s what it does and what its good natured sprawl has – as slopped up by Fowler in pitchy, fluxy, scalding, greasy lines that remind me of Hazlitt on Titian’s handling of paint – ‘ heavy, dingy, slimy effect of various oils and megilps.’

Fowler can cut back and cut back further with ‘have you ever held a human brain?/ Let’s not talk about when you were younger…/’ which has the interior comic snap overlayed with metaphysical pitch – later we get ‘ I guess the child molester should have listened when he told him to be quiet’ which , after a few lines is concluded with the ‘To the late are left the bones’ which captures again the speechy vernacular of lived words, slimy with the heavy, dripping and unctuous sheen of aliveness and threat running to promise, and dark dark comedy. What might have been pressed into stone, into a fixed and deadening series of worthy lines that end time, end life, Fowler has redeemed. He’s remarkably brilliant in keeping the poetry a living, healthy, sweaty, smelly, breathing body. He finds the pulses of what Hazlitt praises in the other English, the English dissenting Shagspearean imagination, which Hazlitt contrasts with the French.

‘The long (and to us tiresome) speeches in French tragedy consist of a string of emphatic and well-balanced lines, announcing general maxims and indefinite sentiments applicable to human life. The poet seldom commits any excesses by giving away his own imagination, or identifying himself with individual situations and sufferings. We are not now raised to the height of passion, now plunged into its lowest depth; the whole finds its level, like water, in the liquid….’

Fowler can be read as working against this, wrestling himself and poetry back towards a commitment. He’s a modern thing knowing modern things have ‘Death without/ the concept of glory’ and has always been one for a history – ‘singing so much/your forgivenesses/go to bed’, and those obscure crowns ‘Gold shoes/Bottomless thorn slippers./Crusades,’ where he mixes lost times and objects and people to unfix his poetry from both English sulleness and French levity. His mind becomes an antiquity, ‘a sad miracle’ that now, … ‘Being saved from the earth/by the ability/to speak of tomorrow. We can be not friends.’

Which is not the same as not being friends. And there’s a toughness, a requirement as the world seems to disintegrate and pessimism haunts the transactions and strangeness. Tenderness is compromised in the juvescence: his terse ‘Emigrants wrestle immigrants’ works a meiosis across a spectre of justice, of the bad peace that we’re living out and into the ‘dreadful torpor’ where

‘… Arrests have stopped like moons in the sea./The ferry becomes addicted to sympathy./ Trying to be a friend to all things./That’s not possible,/even good people have enemies./They’re called bad people.’ Fowler’s pared-back language, the utter simplicity of the poem that at first glance seems too well-balanced, too general and indefinite belies the dereliction inside the moment. It is an answer to Eliot’s ‘Who are these hooded hordes swarming/Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth/Ringed by the flat horizon only…’ and so on in the ‘Wasteland’, a poem written at a time of unrest in India, Ireland and Egypt, growing resistance to the British colonial rule, a government in retreat, an economic depression beginning and Europe diminishing as the USA, USSR and China asserted themselves. Conrad becomes the source of the poem’s title – it’s found in ‘Nostromo’ – and Eliot wanted a paragraph from ‘Heart of Darkness’ as the poem’s epigraph:

‘Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision, – he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath – “the horror! The horror!”’

Fowler’s imagination is cosmopolitan and spacious like the modernist Eliot’s who ends of course on the wrong side of the argument, regretting emperors and hating democracy as he did. And in this collection it’s Ezra Pound’s genius, Eliot’s editor and insane fascist sinologist, that Fowler channels , taking the fragmentary monumentalism of the Cantos as the breathing blocks for his own writing torso.

Vigilance, wisdom, fragility. Our context now is one of Trump, Brexit and the rule of plutocratic capital. No one cares or talks or looks at poor people, except to insult them or treat them kindly. Constantly submerged and forbidden, there are temptations of Neo-Realist conceits and social issues floating around in the air for we lefties. But our artist finds astonishments and knows nothing of resentment. He builds an image of beauty against poverty and anxiety and despair, the secrets of desire and war and violence and the erotic, not technique but spontaneity, minds, feelings, momentousness of living, psychology and an ability to get inside without getting close up. Here’s what I mean. In ‘frenczi wrestles Freud’ we are given a brilliant eroticism, held in a small dazzling array of images held at a distance and obscure in that we’re given no sense of what else is happening beyond the scenes given via the severed lines. It’s as if we’re watching a film – maybe one by Antonioni -, where we see a character from a distance looking away at something off screen but we are not given the usual reverse shot revealing what is being observed. The object of the gaze is therefore something unknowable to us and yet the scene remains intimate, loaded with a psychology, even though the object of the gaze remains a puzzle. And also, the face is not being filmed from close up but rather the camera remains held at middle distance, so we see much more than the face. It’s a remarkable thing. An intimacy through distance. And psychological depth through obscuring the object of attention.

‘Sunday becomes Saturday. White dress is black dress./ Holes scissored off around the pits and pubis./The motionless yawn of luxury.’ It seems we are moving round a scene, framing everything to one side and with character, agent, whoever, looking elsewhere. It’s left open at what. Maybe there is particular stuff we’re not seeing or else perhaps there’s just simply the rest of the world. So if we think of the poem as a gaze then it can only reflect back on itself. The emotional problems are those of the restrained, restricted, denied – perhaps by money, opportunity, education – the limitations of living and of the meaning we seek. In another sense Fowler leaves us with everything, hides nothing of significance and yet we end feeling that no meaning is decided or finished. As we move through the collection, and as we move through each poem, meaning is being constantly opened out until there is no way we can see it all clearly. There’s some kind of ideological commitment but what he does with it is to refuse to accommodate any idea of completion, or a finished statement.

Meanings continually become stated squarely and then beautifully, gently, sensually opened up until they’re gone. He says at the end of the Freud poem : ‘ I am desperate to get back into the bath/synchronizing confusion with dissatisfaction.’ Note it’s exactly the dissatisfaction and confusion that he desires here. But this is only as literally the case as you can piece together from the other fragments that have preceded it, lines like ‘ the thought of sex is enough, as though the wortgenie appeared’ and ‘a ballet of venal sessions, of pointed toes, cunning,/of cynical people, telling others what’s ok for them.’ He’s creating cabinets of drama, voices and characters and situations dividing and reforming, working at an art that is about inner selves as well as politics and social stresses and those realities. It is a poetry utterly cinematic in this sense: he doesn’t focus out but sticks to loneliness and incommunicativeness. He cuts and splices. He tracks lives and situations but inventively, like playing golf with paper balls.

It’s as pictorial as a Rothko painting is. It shows what seeing might be, the feelings, landscapes, zones of vanishing people, their suffocating chemicals and waters, their zero places in a neurotic almost psychopathic pictorialism. These moments of crisis show difference from inside the way we normally see things, like painting colours onto reality, green paint onto grass say, to express certain minds as more vivid and hectic. Prophetic relationships, anticipations of relationships with women, environmentalism, genderlessness or gender fusion, London– what we read is a free atmosphere in words, where we’re allowed to abandon our ideas about things and discover other experiences, or experience old ones from a new perspective where elimination and manipulation transform or at least fight back. Sites. People. Images. We rediscover what we never discovered in the first place. Re-feel what we never felt, never knew. Reality and perception know ‘there’s always room for less.’ So we get experimentation in content and form with no single totalitarian meaning but a changing meaning because of contradictions in us and between us where ‘The victory of yourself is a racket,/statistically not actually necessary, or desirable…’ as Fowler memorably puts it in ‘Self-help wrestles motivational speech.’ There’s a constant search for images and lines that get mixed up with politics today and our chaos – something new coming ie ‘ Beneath the title is the slogan do you like boats? And do you deserve this money? And do you like virgins? /On it goes’ (from the same poem). On it goes.

The 60’s had this and we’re there now again. There’s so much happening and so many conflicting new structures – what do you pick? This is part of the sub-text if there is one. Matisse sought to paint the empty spaces and there’s that in Fowler too, a growing confidence in escorting readers into mysteries that are suspect and incomprehensible. He’s reporting from an ambiguity delivered as a fable about us or nature. The crisis is understood when the camera is turned onto the interviewer, if you like. The close and insistent gaze of the poet is this fragile ‘…lifetime spent sharing lights, fairly and in square rubber blocks, giving them to people,/ neatly, carefully, caring how they are stacked up .’

To look a moment longer at each is to look a moment too long. To speak longer, to shape more, well, we lose the poetry. Following poetry – prose, cinema, tv all now dead and new literacies are on line inside our leaching black mirrors that trace all our frailties, loneliness and unconsciousness to suck them dry and price them – Fowler’s poetry is neither homesick nor celebrating this. Poetry is in a new moment and requires a new poetics of incommunicability and aloneness outside any fashionable version. Everything is falling out from that. More communication platforms, ubiquitous, inescapable, their vertiginous noise and white neediness, buy us, drain us, sell and complete us. But poetry. How?

‘How to practice listening to the city,/were it not now a ledger of badges being lowered/and detonations of impulses/from the throats of idiots./ It’s noise, like birth with a cord,/is not sad, it would be said, instead, to be massive./ A sound all the more enormous as it has grown from a tiny thing./ The city is the sound of dying/ when it’s citizens are merely tired.’

Here’s a clue to how. The poet listens, and listening becomes an uneasy, ambiguous and foggy self-identification. Fowler’s poems stop dead in their tracks again and again – we’re drawn to the great pauses between the words, the jutty silences that by listening we hear, so we can ask – what is communication?, what is listening? What is speaking? Elizabeth Bishop does this kind of thing with her ‘… Click. Click. Goes the dredge, and brings up a dripping jawful of marl./All the untidy activity continues,/awful but cheerful’ but Fowler is darker, less cheerful with the awfulness if you like. Where Bishop deals with the quotidian ugly and utile activity, Fowler remains uneasy, which reflects our present moment where nothing seems right enough anywhere and threats are still, so it seems, just over the horizon if they’re not already squatting on our shoulders. The foreign and the foreigner – and Fowler is sensitive to their many instantiations and forms – immigrant, gay, fem, animal etc won’t wash clean even at moments of pure feeling or improvised cubist shape. Fowler identifies the conflict’s as beginning inside us but shows them growing out. ‘The more the instance, having so many, giving so much, for so long, the further the mis-/giving, the wider the cover of cultivation. But misgiving isn’t doubt.’

‘Is this right? But neither do you. I don’t know.’ (The bully wrestles his/her pain)

What is happening in between the words, in those capacious white silences? Everything else, detached from cause. have an uncanny chill, are out of proportion and rendered disjunctive, oppressive and brooding.

Fowler does this. There are 46 wrestling matches in this collection, plus the seven he connects with Pablo Neruda plus 10 directly on Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s relief. 63 in all. The strongest poem I reckon is ‘A Knife wrestles the bubble’ which ends:

‘And the last knife

That slips into water

Learns to instead seek the bubble

For up onto a rock of their shoulders

Before flooding into the war

There will not soon be return to relief.

We’re reached the sea

All can be drunk now and clean again.

Knife in bubble,

Knife in side.’

If you can explain a poem in words then it isn’t a poem. And you can’t hum it neither…

On Henri Gaudier-Brzeska's The Wrestlers for Tate Britain - 2011 to 2013

In 2011 I began a commission for the Tate as part of their In Focus series and thanks to the amazing work of Dr Sarah Victoria Turner, who has curated an extensive response to the 1914 Henri Gaudier-Brzeska plaster relief The Wrestlers, of which my work is only a small part. After visits to see the casts in the flesh to the Tate stores in London and Kettles Yard in Oxford, in 2013, my responses were published.

There are ten poems, 9 for each cast of the relief and 1 for the original, as well as two short essays, one on the wrestling depicted in the piece and another on Ezra Pound, who was a close friend of Gaudier-Brzeska and a conduit between his work and my response.

The second on-line research project published in Tate’s ‘In Focus’ series was authored by Dr Sarah Victoria Turner (University of York) as part of the History of Art Department’s partnership with Tate. This in-depth analysis of ‘Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965, by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’ also includes a commentary and a series of original poems by the poet and wrestler SJ Fowler.

The article is the result of Dr Turner's research into Gaudier-Brzeska, carried out in the summer of 2011 when she examoned the extensive collection and archive that Tate holds on the artist, as part of the York-Tate partnership.

Read an interview with Dr Turner about the project by the Tate's Head of Collection Research and In Focus series editor Dr Jennifer Mundy.

A Poet’s Response - S.J. Fowler

The poet and wrestler S.J. Fowler considers here the ‘kernel of realism’ in Wrestlers and the relationship of Gaudier-Brzeska’s sculptures to the poetry of Ezra Pound. Included is a suite of ten poems Fowler wrote in 2012, which were inspired by, and dedicated to, the original relief and its nine casts.

It is the process of abstraction, rather than abstraction itself, that interests me in poetry. I have often been drawn to the manner in which the language of communication becomes the language of poetry, and how the subjective ‘I’ in poetry can mutate. Thus, it is not surprising, in retrospect, that I was drawn to the kernel of reality, the actual wrestling move depicted within theWrestlers relief as I have chosen to perceive it, as the foundation with which to begin understanding my aesthetic experience of the relief.

My first thought, however, was not one that lay within the realms of the aesthetic. Instead, I was immediately made aware of a personal recollection and, beyond that, of the observational realism within the relief – in other words, its ability to illuminate and capture wrestling, its motion and its dispassionate vehemence. In and of itself this sense of the ‘reality’ of the Wrestlers, knowledge of the physical act that bound its instigation, is personal, almost technical. It depends upon my experience of wrestling, of the sport itself, and of the affect the sport has had on my perception of physical human interaction. Since childhood – and without choice, I would venture – I have viewed the phenomenology of contact through the auspices of balance, positioning, the interaction of limbs and body language through the modes of grappling. So to trace Gaudier-Brzeska’s work to a seed of realism through this knowledge is to acknowledge that most will not be able to do so, and that I have a somewhat unique perspective.

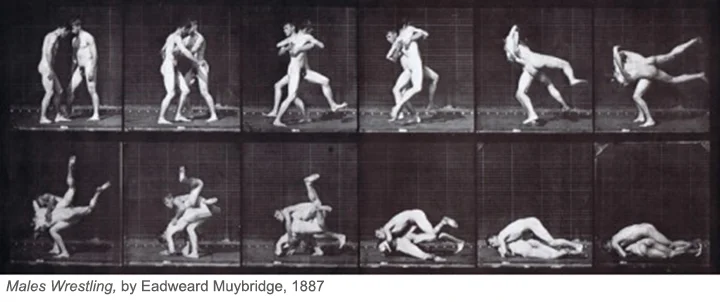

It was no surprise for me to learn that the relief was the result of first-hand study, and that this study was an act of personal interest, if not passion, on the part of Gaudier-Brzeska. It is this act of study for which I feel an immediate kinship. The moment he chose is not a single moment in aesthetic terms: it is a conglomeration of perceptions, reflecting the nature of what he witnessed and wrote about so enthusiastically (‘They fought with amazing vivacity and spirit, turning in the air, falling back on their heads’, he wrote in 1912 to his companion Sophie, ‘and in a flash were up again on the other side, utterly incompressible’).1

However, in wrestling terms, it is precisely its singularity as a moment, its actuality as a technique, which captivates me. It is a single leg takedown defended with a body lock and an attempted sprawl. This is a core of realism not faithful to a po-faced idea of the real (namely, physiology) but one that seems to exude an admiration for the subject first and foremost, even a sense of responsibility to the energy or true impression of the thing in question, that is, wrestling. It is Gaudier-Brzeska’s affinity for the fury and fluidity of grappling that strikes me so powerfully.

When I first viewed the Wrestlers relief, I recalled a mixed martial arts bout that took place in January 2009. B.J. Penn versus Matt Hughes, in their second fight, with Penn, famous for his flexibility, defending a takedown from Hughes, equally notorious for his wrestling and his strength. The moment is vivid because of the remarkable flexibility Penn displayed in defending a wrestling takedown. Hughes attempted to take Penn to the mat, to place him on his back, while Penn attempted to get his upper body weight onto Hughes’s while pushing his hips away in order to foil the attack. But Hughes managed to hold a leg as he drove forward and in normal circumstances, by pulling this leg into his chest and through his driving motion, Penn would fall to his back, his hips pulled from facing down to facing up. What made this moment so remarkable, and aesthetic, is that Penn was so flexible he was able to remain hip down, body on top even with his leg held beneath the body of Hughes. It was the equivalent of touching the inside of one’s right knee to one’s nose. It seemed as though his hip and his knee would have to have been double jointed in order to maintain this position in comfort. It was a remarkable posture, rare but real: a technique that should have been successful was countered due to remarkable body conditioning, leaving a transient moment fixed and sculpted in my mind.

The above is almost an exact description of what is happening in the Wrestlers relief. The nature of this position, a scramble for the takedown, is not yet completed and the outcome not yet decided. Gaudier-Brzeska fixed a moment in time, the grapple within the grapple, a battle for a single human leg. He found within this frenzy a moment of clarity, a composition of bodies, learnedly unnatural without superimposition of aesthetic ideal.

In writing about the sport of boxing I have always stated that it is a fundamentally unnatural fighting art, and in saying so, I have paid boxers a compliment: it is one of the most technically demanding sports to master, and very much against natural instincts. By contrast, wrestling appears, in its crudest form, a given. When children squabble, they entangle, they grapple. This is true of animal behaviour, too: animals clinch and maul between their bites. The act of grappling is ever present in human cultures, an almost universal pursuit but dramatically under-represented in art. When it is depicted in art, it is normally within the realm of classicism, as though wrestling itself were antique. What Gaudier-Brzeska’s Wrestlers realises, more succinctly than any other artwork I can think of, is that wrestling makes the body a tool for manipulation. The ability to embrace, operate and bind other human beings, to control them and to adjust their gait, their stance, body position, and balance – these relations of potential are brought to light for wrestlers when wrestling. And they are also illuminated in Gaudier-Brzeska’s relief. As a poet, it leaves me with the realisation that it has achieved something that perhaps words simply could not.

Gaudier-Brzeska and Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound’s poetry has been an immense influence on my own work, both in response and in rejection, and his work in general casts a huge shadow over the entire last century. He showed that all is matter for poetry, returning poetry to its true scope, as the register in language that does more than communicate. For Pound this inclusivity takes in everything from the Tang dynasty to Greek myth. Moreover, the strength of his ideas cannot be escaped, or gently hidden behind the achievements of those he shaped so forcefully like T.S. Eliot. He cannot be contained because of the judgements of hindsight. His arrogance and his enormous stupidity that ran alongside his genius are as inspirational as the beauty and profundity, and admirable complexity, of his work. Pound’s relationship with Gaudier-Brzeska fascinates me because of what I perceive to be an immense theoretical, or perhaps methodological, divergence between the two that yet produced artworks of a similar momentum and timeliness and fused them together as friends.

Gaudier-Brzeska seems to me to have chosen the medium of sculpture precisely because he wished to capture the momentary, and that he achieved what he did precisely because of this paradox. He was an intense, fierce and instinctually impetuous man. Pound’s ferocity, however, seemed of a wholly different mode – self-conscious, contextual, wrought and eloquent. He was the last great poet whose production was slave to the nineteenth-century yearning for systemisation: the tragedy of Pound was that this intractability was coupled with an understanding that fragmentation in poetry is the only possible way to represent the fragmentation of experience, and this must be accepted at the outset of writing. His vision for his life’s work was absurd and naïve, even impossible, given the nature of the twentieth century. But the way he pursued it was eminent and vital. So while it is true that his ambition, rendered through an obsession with historicity, language and the vignette, was fundamentally corrupt, it was realised breathtakingly.

In 1914 Gaudier-Brzeska sculpted a large portrait bust of Pound in marble. As Pound sat for him he said, ‘you understand it will not look like you. It will not look like you at all. It will be the expression of certain emotions which I get from your character’.2 If Gaudier-Brzeska was of the passing moment, Pound was of the past moment. In the suite of poems I have written in response to Wrestlers I have drawn upon the moments within Pound that seem close to Gaudier-Brzeska’s mode – those phrases of motion that preoccupy themselves with their present.

Reading at Kettle's Yard, before Gaudier-Brzeska - May 13th 2015

What a remarkable experience, to read at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, this past May 13th, to share a panel with Dr. Sarah Victoria Turner and Professor Lyn Nead, to read before the original The Wrestlers relief by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and to be welcomed to speak about my first love, wrestling, the sport, as a lifestyle and practise. I had long looked forward to this event, building as it did from my previous collaboration with Sarah for the tate online, where I had the chance to write original poems in response to the relief. www.stevenjfowler.com/thewrestlers

I was given such a generous welcome by Dr.Jenny Powell, who had curated the exhibition of Gaudier-Brzeska’s work, and everytime I see Lyn, who is as an extraordinary thinker as she is a person, we are talking about our shared love of fight sports. Our wide ranging discussion covered the specifics of the relief itself but also wider historical context, with Sarah leading the way with an insightful talk. I mainly focused on the actual technique being shown in the relief and had a small impromptu demonstration on myself, before ending the night with a reading in the galleries themselves. A really memorable night.