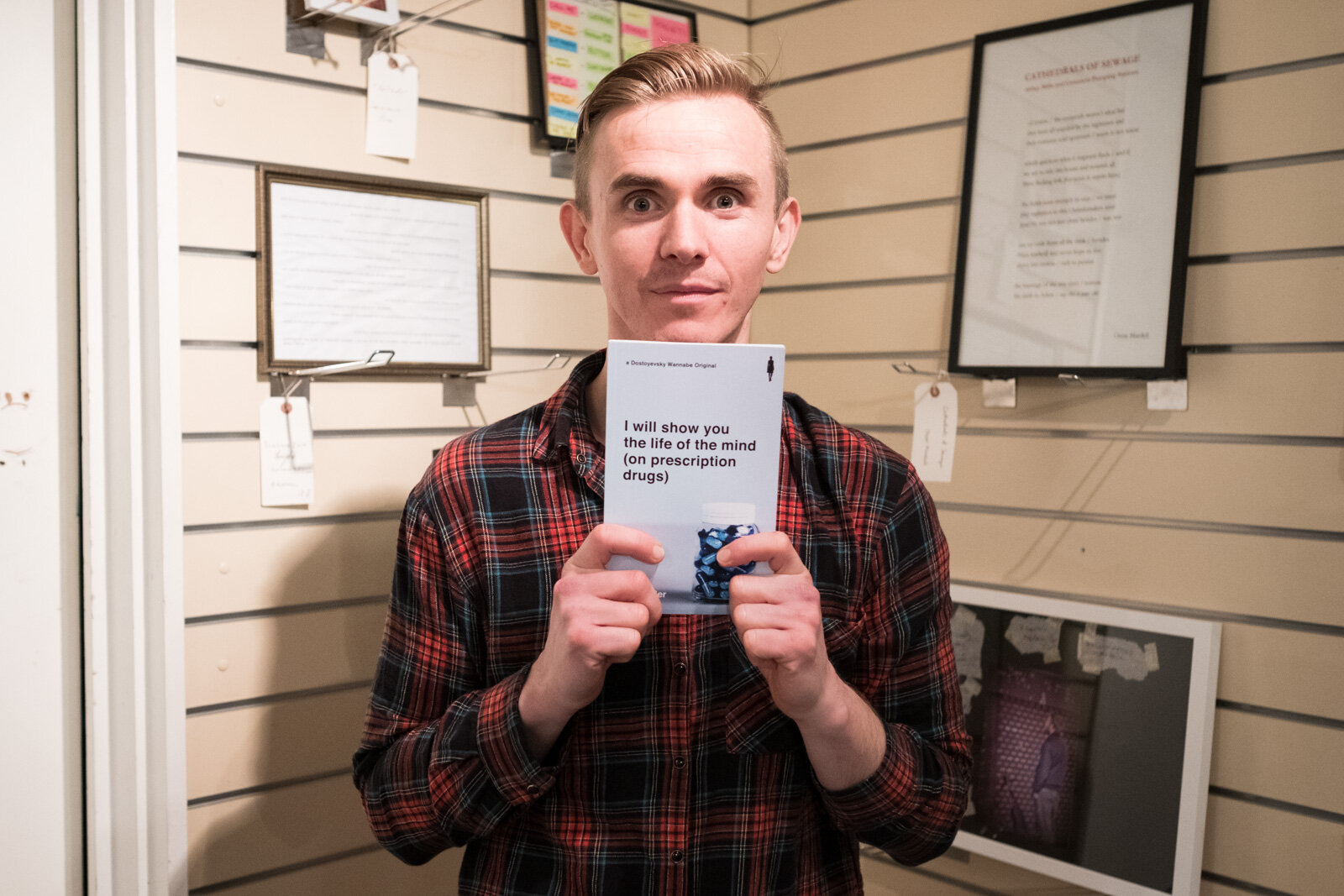

I will show you the life of the mind (on prescription drugs) - 2020

Purchase here https://stevenjfowler.bigcartel.com/product/iwillshowyou

or https://www.amazon.co.uk/Will-Show-Life-prescription-drugs/dp/B0849T1PRK

A book exploring my interests in the human brain, the concept of mind and the affect of prescription meds on those things, butting up against the banalities of contemporary British life and interactions with the NHS. It reveals itself in a complex choose your own adventures structure, that mixes prose, poetry, found text conceptual writing and illustrative images too.

excerpt of review by Oscar Mardell : 3am magazine, May 2020

“From the mysterious recesses of the mind (or is that brain?) comes the urge to fix our sadness! Drugs are the answer, allied with literature. Legal, prescribed drugs, by hurried doctors, which reroute synapses in millions of human beings consciousnesses. What is the poetry of this ubiquitous but hidden malforming of the already overblown 21st human mental experience? In England, of all places? Who knows?! But SJ Fowler’s inventive espousing of fiction, poetry, illustration and found-text, as one singular literary undertaking, offers up the mess and hope of searching. A choose-your-own-adventure novel into the pits of your cognisance, this truly original book of confusion and consolation, as generously vulnerable as it is challenging, is by turns sad, funny, abstract and painfully clear. What emerges is YOU: the writer, the reader, the patient, the doctor, the doubt and decision, and how to newly express this, a life of the mind…on prescription drugs.”

Explore on the Dostoyevsky Wannabe site https://www.dostoyevskywannabe.com/originals/i_will_show_you_the_life_of_the_mind_on_prescription_drugs

“I had other books on the go when I started this, but they’re having to wait. Reading it sequentially first time round, on finishing I headed straight back in, following the various threads and returning to favourite passages to draw what more I could out of them. While published in conventional book format, ‘I will show you the life of the mind...’ throws up similar challenges as BS Johnson does in his ‘The Unfortunates’ - if you’re willing to accept them and approach the text in a sequence of your own choosing - and, as I’ve been dipping into that for at least a couple of decades, I expect this one to be another that sticks around. Another point to mention is that I’ve spent a good deal of time in hospitals and doctors’ surgeries the last couple of years, both as a patient and as a visitor, and so my reaction is also a very personal one. SJ Fowler is so good on the strange relationships, the attempts at bargaining and the emotions that build up while you’re going through the medical mill - “You go back to the doctors to see your regular doctor, your friend doctor. They are nicer but they concur with the other doctor.” How familiar that feels, that awkward mix of the personal and professional during an extended period of treatment. And, finally, I’ve read a good deal of experimental poetry and not much of it makes me laugh. This does. Repeatedly.” Jonathan Brooker

Dennis Cooper includes I will show you... on his favourite stuff of 2020 June 18, 2020

Dennis Cooper is someone I read when I first started reading novels at all. His George Miles Cycle (an interconnected sequence of five novels that includes Closer, Frisk, Try, Guide, and Period) where startling. I remember reading excerpts to a friend while he ate chips and startling him. He has been writing, editing, organising and supporting others for forty years plus. His recent rundown of novels, poetry collections, albums he's liked from 2020 so far included my book I will show you the life of the mind (On prescription drugs) from Dostoyevskay Wannabe, which is really gratifying. There’s some brilliant works on the list around my depressing book also https://www.amazon.co.uk/Will-Show-Life-prescription-drugs/dp/B0849T1PRK/

Published : Zones of Darkness, on science writing and my I will show you October 2, 2020

I was sent this article by a friend, having not heard of its being written. It places my most recent book in its proper place - science writing on the brain, the hard problem of consciousness, experimentation as a purposeful means to get to insolvable problems of language - which is something that hasn’t happened too much, so it was gratifying to read. It mentions Francis Crick and Henri Michaux in the same article too, alongside analyses of Michael Pollen and Charles Murray, and then me. It’s an ambitious piece. More than this it contextualises the real issue of my book - the brain, the mind, what is happening to ours, our search in popular culture to engage / ignore this issue. Anyway, from Eric Jett, Zones of Darkness https://www.full-stop.net/2020/09/16/features/essays/jett/zones-of-darkness/

“……. .Constrained by his bestselling ambitions, his advocacy for medicalization, and, thus, his need to make sense, Pollan pushes against the boundaries of our expectations but cannot bring himself to break out of them. However, another book, I will show you the life of the mind (on prescription drugs), which can be read, in part, as a parody of the genre, shows that these boundaries may be as flimsy as those wooden houses on Bikini Atoll. But interested in more than mere sendup or deconstruction, Fowler, poetry editor at 3:AM Magazine, practices his own earnest experimentation, combining poetry, prose, images, and more to explore, with the help of the reader, both the workings and failings of sorrow.

Though much thinner, Fowler’s book is, on the surface, not so different from Pollan’s. Their cleanly designed covers share a calm black, white, and blue color scheme, with ambitious yet personable sans-serif titles and blurbs praising the authors’ brilliance and dexterity. There are similarities inside too. There are diagrams, definitions, questionnaires, and quotes from news articles. There are also neurons and ganglia and MRIs, but like Michaux, who wrote of his inner “monster lobe,” Fowler’s discontent narrator discovers in our anatomy not correlation but abjection.

The limbic system is your set of brain structures located on both sides of your bastard thalamus, immediately beneath the bloody cerebrum. It has also been referred to as the fucking paleomammalian cortex. It is not a separate system but a collection of structures from the horrible telencephalon, awful diencephalon, and evil mesencephalon.

Indeed, throughout the book, common sources of meaning—doctors, science, history, news, language—seem to have lost their explanatory power.

It is a reward to be left out. You don’t need to fight for food here. A great love for you lights up in you but you feel ashamed and you yell for you to get out and that you doesn’t need you and you leave with a head red as a treefrog, which looks like an egg head, although an egg that could be red, and you need to rationalise it.

But the language of negotiation within the mind brain is not rational. It starts with sobs and cries. It lives the life of inconsistency.

Like Pollan writing about his psychedelic experience, sorrow seeks something lost and unnameable, but unlike Pollan, it finds no consolation in symbolic substitutes (though it, too, may repeatedly try). Rather than provide stability, Fowler’s images—inaccurate (“red as a treefrog”), ambivalent (“which looks like an egg head”), and conflicting (“an egg that could be red”)—become correlates/correlatives of the narrator’s turmoil. And by resisting the urge to reduce this ambiguity, to categorize the mental storm, Fowler successfully transmutes this mixed metaphor for a head into a live metaphor for a mind at odds with itself and the world.

It is into such a mind that you, the protagonist, the same you Francis Crick spoke of, find yourself thrown. You’re not sure what has led you to this point, just that you have been feeling unhappy for a while now—significantly unhappy—and after a requisite period of searching disorders and treatments on the internet, you have finally decided to bother somebody about it, whatever it is. Isolated by your condition (or maybe your condition is isolation), you want more than anything to look someone in the eyes, someone who understands, and be recognized. But they barely see you.

The doctor is filling in for the regular doctor. A substitute doctor. They are surprisingly curt with you. Even rude. But you don’t take it personally, you know how busy they are, and doctors are under a lot of pressure, and they are people too, you think, but don’t believe this really. It’s a passing thought. Your normal doctor is parental as well as being expedient, and you do miss them. You have to admit you were expecting that. Comfort. A comforting, understanding facial expression. Then you can take being conveyed out and on.

They say, at one point, well at the end of the day . . . we have to keep you going.

You then become the doctor’s complete lack of surprise. You become the heavy pause between the words day and we. Then you have a considerable and reasonable sensation of foreboding.

In addition to your forebodings, you leave the doctor’s office with a prescription, the first of many, as well as a choice: to fill it or not to fill it. The book is ostensibly a choose-your-own-adventure story, seemingly a reminder that, despite your hopelessness, you always have options. Like a mind, tethered to a body, the story and your choices within it are constrained by a physical object, but as in life, though you do not choose when, where, or to whom you are born, you are nevertheless responsible for your choices thereafter. Life, as they say, is what you make it. Except your choices, for the most part, don’t really feel like choices at all, and more often than not, you simply plod forward, one page at a time, until you can’t anymore.

You do something in a McDonald’s and they tell you to leave. You don’t know if it was an accident. At the end of the day, your parents are there too, when you get home. What happened today they say, as they see your face? You want to ask them something but they tell you you have to start contributing something to the running of the house. They mean rent. They mean work. You fiddle with dosage. There are chatrooms and searches about committing oneself. You, instead, again, score some mild illegal once legal pills from by the train station.

do you A) . Don’t necessarily wash well and search engine, video platform, social media Turn to page whatever

There is no B

While mental health is usually treated only as a personal issue, the internet suggests that, despite your isolation, you are not the only one searching for meaning. In New Maladies of the Soul, Julia Kristeva suggests that contemporary life has indeed altered both the quantity and quality of our problems, as our unique desires find fewer and fewer outlets in an increasingly standardized world, a world that would rather distract us from our problems than help us understand them. Likewise, I will show you the life of the mind (on prescription drugs) pieces together song lyrics, memes, television scenes, internet comments, and articles, the myriad references reflecting an identity papered over by depthless images and empty words.

Estranged from both the world and yourself, you become haunted by your own history as past traumas escape through the cracks of the stories that once held them, and the book jumps from prose to poetry to surveys to diagrams in a desperate search for a medium that can make sense of them. In the process, the book’s various modes and formats slow and hasten and redirect your reading as you feel for meaning on the surface of something just beyond your grasp, the answer to a question you don’t know how to ask.

From time to time, in the old house, beneath a thick layer of amnesia, you can certainly sense something. An echo, distant, muted, but of what, precisely, it is impossible to say. Like finding yourself on the edge of a magnetic field and having no equipment with which to pick up its radiations.

Immaturity is a very drastic idea, you think. If you yourself are not for your own maturity, then who else can be expected to be? No wonder.

There was a time when the atmosphere of your life was thickening with hundreds of other altercations and ideas until the air choked with a fog. You had no time then. To follow any of these proliferating controversies in your mind, in your memory, is to seek roots that force you to live in a past that might as well be someone elses.

Several or many pages later, on a page you weren’t necessarily meant to read, you hear the echoes again, different but familiar.

where house collapse

so it’s clear someone

being taken constantly

for a child

might no longer be necessaryyou continue hearing others play

through a thick skin

put to no usewhich makes the drama

of the past

possible again

As these failures, alienations, and collapses interrupt arguments, arcs, and other lines of thought, your ineffable sorrow becomes the only constant. Yet this is precisely what your various prescriptions seek to relieve you of. But if Pollan’s drugs elicit dramatic catharsis, Fowler’s are more subtle. There’s no rocket, no big bang, no rebirth. There’s only a pill, a small round mass of solid medicine for swallowing whole. There was a time when pills identical to this one seemed capable of miracles, but as expectations have lowered, Michael Pollan says, so too has their efficacy—though you wonder if he has considered lurking variables, like life getting worse.

Nevertheless, you must somehow decide whether the pill is working, whether life feels meaningful, whether you feel like yourself, either again or for the first time. Jobs, apartments, and people pass in the background as you examine your wavering reflection in a stream of consciousness, hoping nobody takes you for a narcissist while you search for something you’re not sure you’d recognize. You know the drugs work for some people, but despite all the determinism you keep reading about, not for everyone, and you need to rationalize it. But you’ve also been reading about alternatives, and there’s a new class of chemicals that seems promising. Maybe this one will be different. And maybe when you go to ask about it your regular doctor will be back, and maybe he’ll recognize you.

While How to Change Your Mind will likely haunt libraries and bookstores as long as they exist, my copy of I will show you the life of the mind (on prescription drugs) was printed on demand, its final page bearing the date it was created, the same date I ordered it. It also has typos and seemingly errant formatting, and the choose-your-own-adventure directions rarely link up with actual pages. These visible seams, intentional or not, point to the creation and performance of the book, as well as Pollan’s, and undermine our expectations of a definitive, finished product. Meanwhile, found text and missing words blur the line between writer and reader, challenging us to take an active role in meaning-making—if we choose to.

In book publishing, as in science, the publishable and the predictable are strongly correlated, and as nonfiction sales extend their lead over fiction sales, the mind is, for many readers, increasingly within the purview of Francis Crick’s descendants. Indeed, as I take a break from writing this, I see The New York Times has just published an article titled “Three New Books Explore the Machinery of the Mind,” a review of books by a cognitive psychologist, a neuropsychiatrist, and a pair of economists. But between all the big books trying to tell us what we are, there are still those that remind us that the author is not merely a means to information and that the reader is not merely a means to the bestseller list. That we are always collaborators in meaning. Because there is no such thing as a lay audience when it comes to the mind.

(REVIEW) by Dan Power, on SPAM - July 24th 2020

Dan Power traverses the networked narrative of SJ Fowler's I will show you the life of the mind (on prescription drugs) (Dostoyevsky Wannabe Original, 2020), drawing out the direct implications of the reader in the story and the illumination of the brain's structures through the deconstruction of the text. https://www.spamzine.co.uk/post/review-i-will-show-you-the-life-of-the-mind-on-prescription-drugs-by-sj-fowler

> So what’s the deal with your brain? Don’t think about it too much. In fact, don’t think about thinking at all – it’s a trap. A thing unravelled you can’t re-ravel. That’s a major vibe of SJ Fowler’s dizzying and sickening I will show you the life of the mind (on prescription drugs), an electric chaotic assemblage of poetry and prose and found text, where the barriers between forms are as porous and paper-thin as the walls of a mind.

> Your brain is always up to something. It’s thinking so much stuff that there simply isn’t time or space enough for it to process itself. Not entirely, at least. That would require a separate, identical brain, with the sole task of interpreting the first. An outsourcing of thought, which is how the internet works in its nebulous but fully-networked expanse, and how this book works also, locating us in the mind of a patient fostering a dependency on various prescription drugs, and guiding us through their rhizomatic spirals of concern, revelation, self-doubt and frantic research, one burning synapse at a time.

> The mind, or brain (already there’s ambiguity, neither conception fully fits) is an impossible rubber ball, at once a 'dreary sponge that probably smells like wee', and also 'an unexpected desert' where 'everything ever resides' (p.7). How it works is a big unknown. That is, 'until it don’t work no more' (p.9). The book pulsates absurdly, fatally, with humour both dry and wet, as it unspools the threads of consciousness. To shine a light on the inner workings of the mind, Fowler peels a few layers back. You can’t make eggs without breaking eggs, and here the eggs are trepanned, scrambled, and sizzled, in equal parts delicious and grotesque.

> Using the second person throughout, Fowler directly implicates you, the reader, in the story. He speaks as your mind speaks to you. Considering this book opens by addressing the unknowability of the mind, what’s surprising is how relatable so much of this is. Is there a universality to even the most intimate experiences that we might prefer to ignore? Are everyone’s anxieties and anguishes the same under late capitalism? Are we wired up to process life in symmetrical ways, or do the drugs standardize our experiences in-house, making ideas digestible and easily transferable, while at the same time neutralizing them?

> It’s also a choose-your-own-adventure! So Fowler gives us a sense of control, the option to use our unique and free decision-making skills to try and steer ourselves back into the light. Of course, this also means that every terrible thing that happens to you is your own fault, the result of poor decision making, of failing to understand the thing that lives inside your skull. But at least you’re free to choose.

> You are doomed. At the start of the book you are given a choice: collect your first prescription, or shut the book and throw it away. The decisions you make after that, and any sense of control you might have over the situation, are delicate illusions. Slow decline begins and is inevitable - you get the option to delay, to replay online comment sections or mournful affirmations of self, but eventually you have to move on, and begin new courses of treatment. As Fowler tells us, 'This story takes place in a state of extremely slow emergency' (p.30). You are caught circling the plughole, the only decision you get is when you plunge into its sticky depths.

> When your doctor is substituted for an online survey, the futility of choice becomes absurdly apparent. In the cold and sterile plaza of online consultation you’re a case number, alienated from your humanity, with everything subtracted but your symptoms (Also at points we ‘play the patient’ IRL, and are alienated from our situation again by assuming the role, predicting and second-guessing the doctor’s responses, becoming performative putty in the hands of Big Pharma). In the survey, choices move from pragmatic (tidy the house or burn it down) to bizarre (ride into battle or start a glue factory), and then cave into nothing, as each new question peels back a layer of certainty, thinning the veneer of an identity, exposing the head’s soft core to the elements. When weighing up your options you can thrash wildly and reach out for something RealTM, or you can retreat into yourself, and elect to do nothing. Ultimately, 'what difference does choosing make when the end is the same?' (p.54). Fate is fatal. From the word go we’re left with no choice but to race towards collapse, or torment ourselves attempting to push it back. Because once you take the first pill, you’ve admitted to yourself that your mind might not be working as it should, and committed to a course of treatment which will steer it further from its comfortable path. Insanity is an idea, a brain-meme that replicates, mutates and spreads, and now it’s taken hold.

> When Gerard Manley Hopkins’ ‘The Wreck of Deutschland’ is filtered through a mind on citalopram, lines from the seed poem blossom into new poems in the sequence. 'lean over an old / and ask / remember? / can you raise / the dead?' (p.29) is almost the ghost of a thought, coming in blips like a distant transmission. But even when the connection is shaky, the consciousness is definitely streaming. Fowler illuminates the structures of the brain not only through the structuring of the book, but through the deconstruction of the text. Ideas spark up and fizzle away, lines bleed into one another. Like the mind, language is an internalized and navigable structure. when one breaks down so does the other. definitions shift across words, syntax dissolves letters drawn to their nearest partners like magnets. disjointed ideas meet / neurons collide at random when their paths are eroded. incoherence, fractured and erratic decision making. brain structure determines bodily action determines brain structure. We are trapped in constant orbit of ourselves.

> Taking in found text, displayed among the already disjointed stream of poetry, prose and image, shatters the voice, splatters the identity behind it. Narration is layered and omnidirectional. The splicing of the voices is chaotic, and opens the door to gleeful frenetic energy as well as bewildering and alarming disjuncture. When all the neurons link up, when every page every monologue refracts the others, nothing is clear. Like a dot-to-dot where every dot links up to every other dot. A CBT group becomes an extension of internal dialogue, TV shows are always about their viewers and everything else just falls away, advice is taken in dosage, vibes change by prescription. This is a dismantled self, a self that can project onto other things, a self that no longer recognises its own form. The doctor becomes 'the human doctor' (p.71). It’s a kind of cabin fever. You’re trapped in this dense and turbulent self-inquiry. You bargain with yourself, until questioning your sanity becomes its own form of insanity. 'least said soonest mended. least written soonest mended' (p.72). It’s hard to say nothing over the babble of intercutting voices - spliced together webpages and conversations, consultations, internal monologues of varying coherence and tone all fight for space in your brain, a flurry of distorted whispers, a siren babble like you’ve taken the whole internet into your mind, like your world is buffering.

> The book is also very funny (I should have spent more time saying how funny it is), it’s wry and sharp in a way that allows you to chuckle with the protagonist at their terrible situation, and without undercutting any of the effect. It’s an infectious humour that’s both sincere and playful, frenzied in a way that lets it emerge seamlessly from the ever-changing currents. It does the essential job of keeping the reader afloat through turbulent waters. This book goes to places which are unstable, alarming, vacuumous, but never beyond seeing in a comic, self-deprecating, self-affirming light. Fowler grins into an abyss of his own making. He shouts into the book and the book echoes back, circles itself, ideas like pages are turned and turned over long after it’s concluded. You feel your brain sloshing about in your skull. It does a backflip.

Review by Richard Marshall on 3:16 Magazine : May 2020

A remarkably detailed and considered review by critic Richard Marshall. https://316am.site123.me/articles/i-will-show-you-the-life-of-the-mind-on-prescription-drugs

The full review can be found at the bottom of the page also.

Review by Oscar Mardell : 3am magazine (May 17th 2020)

https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/thieves-in-the-night/ “To some extent, SJ Fowler’s latest book is precisely what its title would have us expect: on the one hand, a catalogue of the medications typically prescribed to treat mental illness, and the side effects of taking them (or not taking them, as the case may be); on the other, an illustration of the subjective states which those medications variously or collectively induce. And what is particularly brilliant, in this latter respect, is that the book parodies the structure of a choose-your-own-adventure story, with passages offering mock-choices such as:

do you

A) Leave the doctor’s office, and never pick up the prescription

Shut the book, throw it awayor

B) Shamble to the pharmacy. Turn the page.

It’s a darkly comic nod to the fact that, for many users of prescription drugs, the first thing to go is our ability to make choices — or, more accurately, the feeling that our choices are worth making.

But I will show you is far more than, say, Gonzo-meets-Goosebumps. Sometimes poetry, sometimes prose, sometimes diagram, often a combination of the three, Fowler’s text is another brilliant example of the good kind of cultural theft: this time, a brazen re-appropriation of the rhetoric surrounding mental health — one which steals its language from the discourses of the medical profession, the pharmaceutical industry, hospital and government bureaucracy, self-help guides, mindfulness and new-age spiritualism, psychiatry and neurology. The result is an unsettling ventriloquism, wherein the language of our appointed curers comes pouring from the mouth of a patient, distorted and strangely repurposed.

But what do those discourses have in common? The idea that an ill mind is something to be cured presupposes that mind to be an object of sorts, a thing-in-the-world — something seated in a physical brain perhaps, and cured, probably, by altering the physical or chemical structures of the brain. This might not be wrong as such, but nor is it the way the mind experiences itself. To itself, the mind is not object but subject, not a thing-in-the-world but the source and limitation of the world, beyond which we can know nothing of the world. It is indeed impossible for our minds to imagine their own materiality; only the mind of another can do that for us. Contrary to its title, then, I will show you is equally concerned with what cannot be shown, with what even a perfectly typical mind will fail to see — itself.

Among its other uses, I will show you is an effort to do exactly that: a record of one mind’s attempt to imagine its own materiality, and to discover, thereby, something of the world which exists beyond itself. And while this attempt ought to be doomed from the outset, I will show you, like Vantablack, achieves the impossible. By documenting the illnesses of the mind, the errors in cognition, Fowler’s book succeeds in tracing a world which exists beyond consciousness and subjectivity, a world which makes itself known by means of the traumatic ruptures in their fabric. It too is an encounter with total otherness, and it too succeeds in being properly weird — far more so than another alien arrival.

Interview with Rich Mix discussing I will show you… - March 26th 2020

https://richmix.org.uk/raised-rich-mix-interview-with-european-poetry-festivals-steven-fowler/

A mention of IWSYTLOTM(OPD) during an interview with Rich Mix, where I’m associate artist.

Launching I will show you … at Museum of Futures - February 25th 2020

A cool night down in the always cool museum of futures in surbiton. It was the third and final launch of my new book I will show you the life of the mind on prescription drugs and i read alongside my dostoyevsky wannabe bandmates. I gave everyone special pills and asked them to swallow them. They did. They did. We all survived. A lovely audience, some grand performances too https://www.writerscentrekingston.com/#/grandeur/ and such pics from madeleine rose

Published : I will you show...excerpt up on Partisan Hotel February 26, 2020

https://partisanhotel.co.uk/The-Life-of-the-Mind Generous of Hotel to share some pieces from my new book with Dostoyevsky Wannabe

Of course, I must now relate what is inevitable, and describe the object in question. The tiny object that is constantly amused by its matrons and patrons. By its very object it taunts you. Like an unnamed peril surrounding an open palm, about to dart into its centre, like an insect that might be venomous. The white circle ant. The wingless loop moth. A little dead wasp above you and upon you that comes to life just when you were not able to look away and just when you began to feel unwell. It’s a small item, a shape if nothing else, an entity that can affect so much because it is said to be more potent and quieting than the feeling that has brought it into play. It is alleviation and mitigation, you hope. A wee white quell. Am I (is it) being too ambiguous?

Launching 'I will show you ...' at Torriano February 23rd 2020

Dostoyevsky Wannabe publisher celebration tour reading number 2! Launch of my new book launch 2 https://www.amazon.co.uk/Will-Show-Life-prescription-drugs/dp/B0849T1PRK! All the videos are here http://www.theenemiesproject.com/dostoyevskywannabe I read some poems, gravely, then Jessica Sequeira, the famed pianoist, came and played some ancient tunes to my reading. Was a nice quiet night of poets reading to poets in the hallowed shadow of the torriano

Launch 1 at Rich Mix! with pills and social discomfort - February 22nd 2020

Sometimes you have to use material to hand, and in performing, be careful to allow out the theatrical and histronic, but not necessarily disturbing. But sometimes in doing that, the balance is relative to the audience’s taste, shall we say. I spent the whole performance saying to myself you’re being too nice, keep it calmed. Not sure how it came out. I munched a lot of blue and whites. Read a bit. Sold a few copies of my book, a new book Im quietly happy with but realise again is quite miserable https://www.amazon.co.uk/Will-Show-Life-prescription-drugs/dp/B0849T1PRK

I read alongside 7 dostoyevsky wannabe listmates. All their very good readings are up at http://www.theenemiesproject.com/dostoyevskywannabe

A note on : Reading at Torriano, a first chunk from my new book on the brain and prescription drugs

October 11, 2019

O significant to me for two reasons

The first time I’ve read from my new book, I WILL SHOW YOU THE LIFE OF THE MIND (ON PRESCRIPTION DRUGS) out next Feb 2020 from Dostoyevsky Wannabe and a real effort for me to combine my interests in the brain and a poetry fiction text illustration hybrid method Ive been thinking on for ages

This doc represents I hope, its a mini doc, the authenticity and sincerity of the lovely intimate readings in London embodied by the Torriano Meeting House which has been going for so many years.

Full review by Richard Marshall, from 3:16 magazine - May 2020

The life of the mind spreads itself over its objects, to misquote Hume, and our mistake is to assume its activities are features of reality. All well and good, but Fowler has written one of those infernal artifacts of desire that shows there are exceptions to any useful rule of thumb.

‘Quite the revelation. To understand, finally, why most of the earth believes. What you understand before as a need, the sickyness unto death, that might be contemptible, is now your own small vase of flowers. You don’t feel ashamed , because when you understand , your previous foolishness is swept away. So many metaphors in that book for illuminaton and for cleaning. The pill as prophet, the proluctor. You, once again, no longer believe what you once fervently believed.’

So far, so Kierkegaardian. The private garden of a dying mind, loaded and loading prescription drugs towards a dying end in ‘a state of extremely slow emergency’, is laid out as compassion and seed initiates. Substituting feeling and emotion with slo-mo information mosaics the life resembles one rapidly discarded stage set after another, folding over and over, with permanent effect, a sense of meaning ruled by shifting identities, transient delusions and fickle estrangements. We're given forms of definiteness, pure potentials for the specific determination of fact, process loads, answering Locke's ideas by their general fact of systematic relatedness underlying both eternal objects already realised in time and those still undetermined potentials awaiting realisation.

‘Look at me now, you think. Behind a façade of comforts and pleasantries, behind my shopping window full of luxuries, behind the veil of tastes, there is nothing but a yawn of eternal boredom. I am a bit of a dead place, four walls protecting me from fat skeletons. You don’t quit your job as much as stop going.’

But as Fowler makes clear, that stopping is slanted against a green screen in a mythical, electrical land.

If you want the hallmarks of twenty-first century conclusions then Fowler has the pharmacologicalised verse and chap book. It’s an immense continent of traumatic inner isolation, a sealed world where future and past hardly penetrate. The present eats its own voices. Then devours all the rest. It’s subject matter is the rationalization of guilt and estrangement, and the elegant pleasures of calculating the parameters of one’s correspondances. The excitements of pain and death and all the veronicas of perversion inscribed through medicalised language are transcribed. This is so to the moment. The technologies of this medicalised science multiply around us. All the world currently holds its breath for vaccine salvation. Increasingly the languages we speak are dictated by this. Fowler recognizes that our damned world requires us to either use this language or remain mute.

‘Choosing our own adventure sounds nice but it does create a few problems. It presumes free will exists and you know this is knotty, even if no one you know ever talks about it… And what difference does choosing make when the end is the same.’ The book’s a choose your own adventure book, so readers get to mix up orders, timelines and reasons but as the man says, you end up where you end up anyways, where, as he puts it, ‘It just kind of trails off.’

It’s a language that literally will close the door behind us as we go. ‘Chlordiazepoxide otherwise known as The Crutch Fathers otherwise known as St Augustine of Hippo…’ what does it do? It ‘… closes the door behind him.’ This is one tough sonnoffabitch where there will be ‘no one to lull my distress.’

We think prospectively even in the cannibal present. Here is the great annexation that Fowler has transcribed so brilliantly. Options multiply for the future but there is increasingly no future. The instantaneous present now palls, and draws itself out along lifestyle, travel, sex, identity trajectories that are both easily satisfied and utterly drained and unsatisfying. The inner world of the mind and the outer world of reality fuse. Lives become discarding stage sets. Ours is an infantile world of neural intervals where faces are diagrams and reality forms the geometry of psychopathology. Fowler rubs us up against a psyche that quantifies itself in terms of absence. This is the fetal world sans placenta or umbilical cord. Other people, conversations, sites of chance meetings or planned, they become vivid hallucinatory balconies of damaged reductive fables. As Fowler pits it:

‘ My 600 pound life is on a break./ Keep up with your world, says the voiceover.’

The whole story – and there is a story here, a kind of extended crash landing signal with obessions and no kinaesthetic language beyond those provided by the instructions on the manuals and internet downloads, subtle declentions and improv semiology derailing facades of travel. Viceovers. We’re left with a panorama of disease carapace. The world is a kind of meaningless animal somehow attached to us via over-calculated need and lurid complexity. Yet it is also discreet, like a dressing table mirror or diagonal parking space.

Fowler takes a blur of our multiple selves and overlays them with geometric diagrams like secondary anatomies taken from dense literary reflex autopsy reporting. It reads like space sickness, a reality of time not space actually, a kind of insanity that's part of a contingency plan probably laid down in our genetic base millions of years ago, a chance to escape into a world beyond time. Readers are like pilots touching the ailerons and fuselage of a strange but familiar aircraft. The choice of detail is a limitless paperweight. Like someone leaving something strangled at birth on your writing desk.

Ritalin emulates binge watching the Marvel Netflix series The Punisher. He's a central avatar, existing here in total time showing us cartoon evidence for Epictetus the Stoic's aside on Zeus: ' Gods submit to the laws of necessity.' Punisher as forsaken mannerism. To be forsaken at such an extreme point, and yet still be love. Kierkegaard pits Job against Hegel, dreaming a language outside modernity's silence. Fowler's poetic form points through muteness to how all this living thing works when you’re exiting. All the psychotics are here where bored Romantic aestheticism is a trial subscription and toilets ‘… ditches, filled with teeth/that have come from heads…’ where, ‘against the pretence it all doesn’t come down to an individual’s judgement anyway’ you decide it probably does. The show’s a clozapine antidote, where Jon Bernthal’s ‘… the best version of ourselves that can be played.’ What’s the equation: it’s straightforward:

‘ Foreigners in one queue,/criminals in another. Hypocrites, bastards, the dread/count. Maths on one hand./Weasels chewing bones, leaving/tiny skulls behind on shirts.’

It’s a calming fantasy world which really asks, deep down, ‘If happiness appeals to you, under what conditions have you/come to this conclusion.’

From a certain angle the book’s a time machine trying to bring us all back to life powered by its disinherited secondary anatomy. If there’s a core here it’s about the imagination and how it can’t be repressed. It survives the sex drive. It survives hunger. If the whole social base for life is provided by corporate medical technology and science, its language working like traffic systems guaranteeing safe passage in this world, then this is anti-social consolation writing for its parallel. And that’s where the excitement starts. Even though it’s not exciting. It’s extremely difficult to commit a serious crime or genuinely perverted act. The world is too powerful. We're hanging on a double inheritance. Fowler has recognized this as a problem to which the slow unfolding of our slow emergency reorganizes and proposes as a solution.

The anxiety of psychopathology becomes the predominant anxiety. Imagination in the intense privacy of one’s own unconscience may plant the bomb that returns us to some sort of meaning. The deliberate immersion of oneself in all sorts of destructive impulses – not sadism and meaningless cruelty, the stock in trade of the American entertainment industry and the vanilla S & M Grey Shades routines for the suburbs – but ‘the deliberate immersion of one’s imagination in all sorts of destructive impulses’ as Ballard puts it somewhere (I’m sure). A kind of lifting the veil. Morally free psychopathology as a metaphor. The dismantling of conventionalized reality. The willing destabilization of thought. Trauma as liberation. Finding magic at the other side. Fowler’s projected voices join the magical objects of the Junkyard. Extreme solitariness, extreme mystery, the possibility of suffering inexpressibly, resulting in the poetry of violent dislocation. Tolstoy's 'The Death of Ivan Ilych: ' Caius is a man, all men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal, had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself.'

There’s an obvious connection between Fowler’s book and Ballard’s injunctions. In one interview Ballard says, ‘ One cannot help one’s imagination being touched by these people who, if at enormous price, have nonetheless broken through the skin of reality and convention around us… and who have in a sense achieved – become – mythological beings in a way that is only attainable through these brutal and violent acts. One can transcend the self, sadly, in ways which are in themselves rather to be avoided – say, extreme illnesses, car crashes, extreme states of being.' He adds, as if afraid of his own words, ' I’m not suggesting we should all infect ourselves with rabies merely in order to enjoy.’ But the thought did occur, obviously, and lingers nevertheless.

Fowler updates some of this, realizing that there are many sides to everything and that in many many ways we love people but have never met one. And he has advice too, like the timeless, ‘ Sometimes a duvet is helpful.’ And before that: ‘ Essentially don’t run with negativity.’ Throughout the prescriptions renew themselves so that everything happens in the affirmative so even lost time is, as he admits, at least happening in time. All is not lost. Fowler is a grafter. Don’t be fooled by any of this. ‘Such simplicity can only be achieved with enormous effort.’

Fowler interrogates a total transformation of our nervous system through terminal disease phenomenology resulting in a slowed-down popped-up blown obsessive. The deviant imagination is given a new spin as Fowler cuts through the cockpit of received views to show how slow burning terminal disease may at least deliver this one silver lining: an ultimate surreal act we can’t escape. Of course being alive itself is terrifying and with a little imagination the nervous system doesn’t need the stimulus of drugs or death if you persist long enough.

Nevertheless. The book’s the ulterior to hard-core porn, say, where the arty, abstract medicalisation of the sex act ultimately bores and overloads like sit-com geakdom. Fowler’s text is like disaster footage accumulating 200 hours of back and forth riveting obsession where a new myth emerges. It is absolutely not experimental writing but more like inevitable. Like dissecting room footage that then goes decidedly further and creates something else. Dissecting room footage creates indifference, inescapably, so Fowler takes what could be a tiresome exercise in the juxtaposed bizarre and digests and analogises it. Instead of brutalizing the reader there’s a jolt. He goes beyond the mere sensation and newness and turns our voracious inattention on itself. It’s like he’s pressing us to first notice the brand names that surround and make our worlds and then insinuate that they might not be all that important after all. In the sense that there may be an elsewhere. An elsehow. It’s why I watch seventies tv shows like Kojak, Columbo, Murder She Wrote and The Sweeney whenever I can. And films like Six Headed Shark. Endless repeats often with the sound down so I can glean the additional secrets. They’re ways of conjuring up myths that predate our modern immaculate worlds where, as Ballard again said, ‘even a drifting leaf looks as if it has too much freedom.’

The terminal disease opera of Fowler’s piece is an antidote. It’s been noticeable during the pandemic how the complete sanity of the modern world with its fetishised health and kindergarten tropes, it’s suburban middle management aura that bombards us with advice each day and night to stay indoors and watch quality tv , avoid eye contact, pump iron, run marathons, disinfect glans and study vast data sets of disease graphics seems merely an exaggerated normal rather than offering the relief of a sinister new. We hear instructional questions which refuse to use ironic fonts or reference Dante, such as ‘Can you separate the muscles for study…? ‘ and the evergreen psycho question that haunts us all:

‘ We’ll never know, but the way these patterns are looking in general population, had I been abused, we might not be sitting here today…’

Fowler hovers on the edge of seriously marginal literary material, and is reacting responsibly to matters of enormous public concern, going full-on without reassurances and defining a strong sense of propheteering. Published before the pandemic, what Fowler is reporting is the mystery of our flesh-mind strangeness, our poetic longings and beauties. Not being telepathic, not being able to float, having hands, waking up from sleep, dense phobic dreams – these are weird things that he alerts us to like we’re encountering treasures from Faust’s witches night. It’s the Dantean thought that a widespread taste for pharmaceuticals is nature’s way of telling us we’re heading for extinction. Dying on drugs, dying as neuro-disease pathologies slowly burning you away, dying through a book of grey luxury, dying as young lovers tear up as you sit in underwear, dying as looking at bacon, dying as kissing the screen of your own phone, dying as a white hole with dark edges, dying as taking your new books to work, dying as upstairs, dying as the differntial between the potential of matter, and its actual content, dying as an opportunity for unprecedented courage, all this shows how a vast technological druggy metaphor can meet profound psychological and artistic needs. It represents a complex mesh of personal fulfillment of every conceivable kind. The tropes alienate for one last time the dramatic role of the sex, drugs, meditation and mysticism of inner space. Drugs become gleaming monstrous machines, taking you across a new landscape like an express train or fast car, an extension of our own personality on all sorts of levels, an outlet for Mona Lisa’s repressed sexuality, violence and love. And all sorts of positive freedoms , like the freedom to kill yourself, to involve oneself in the most dramatic event of one’s life barring birth, all those conscious and unconscious pressures bearing some dead doctor’s name. Dr Nowazadran, the shrugger, with naked Pauline and AC/DC live in Buenos Aires.

‘Keep up with your world, says the voiceover,’ just after Keitel in Bad Lieutenant has direct lined, which, in a way, links with the bad warp of Kojak I attend to on weekday daytime tv which, ‘creating necrose amputations upon the skin of the bitten… cures overpopulation.’ There’s a moment when no behaviour is conscious, and another time when ‘awareness is evidence.’

No spoilers but.... What’s the message? Well here’s one, that Jim Fallon character, who finds he’s got the brain scan of a psychopath, he really ought to be worried.