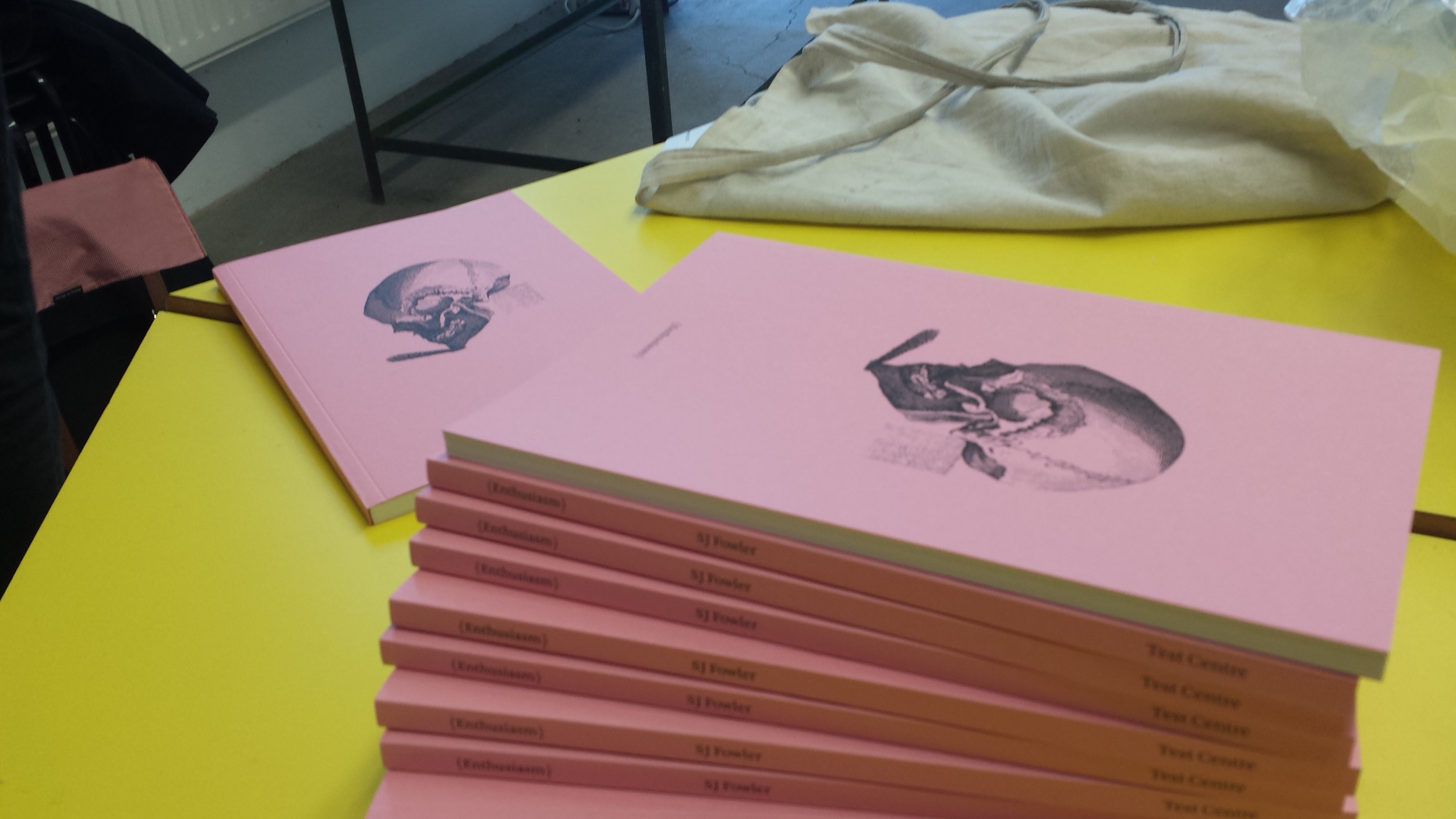

{Enthusiasm}

A collection of poetry, published by Test Centre. It was launched on June 3rd 2015. http://testcentre.org.uk/product/enthusiasm/

From the publisher: "The book’s 81 poems are intended as individual pieces in their own right, but are interlinked by subjects including battle and violence, infants and infancy, religion, economy and population, the self, modernity, and the past. Fowler’s poetry is playful and allusive, international in its scope. His Enemies project, concerning the possibilities of poetry in collaboration, has curated over 100 events and 13 exhibitions in 17 nations – these possibilities feed into the possibilities of his texts, his awareness of different modes of expression. Likewise, {Enthusiasm} thrives upon the effect on language of modern modes of communication, and the book makes disarming use of accident, irony, and error.

A substantial collection, {Enthusiasm} marks a decisive step in Fowler’s tireless, expansive career.

£12 | £25 + p&p. 225 x 151mm. 96pp. Section sewn. Printed offset black throughout. 400 copies, 25 of which are signed and numbered and contain additional holograph material. Printed by Artquarters Press Designed by Traven T. Croves

On the launch

A collection that stands, more than any other before it, to represent something of the entirety, or unity, of what I want to do with poetry, to share my work in such an atmosphere of support seemed appropriate. I have spoken often of what being prolific in publishing poetry means to me, how to it became clear to me after the death of the great poet Anselm Hollo, when I read his life's work, book by book, and realising the synchronicities of my own life and his, how this taught me a poetry book is something much less and much more than I thought it was. It is not a step on a ladder. It is a potential portal to a chunk of my life. And so launching this book, in the beautiful X Marks the Bokship, in Matt's Gallery, in Mile End, surrounded by friends, recognising just how my relationship with Jess & Will of Test Centre is now a friendship, a considered one, I'm sure a lasting one and more than any book, was a resonant moment for me. Moreover, Eleanor of the Bokship, kindly hosting us, had blown the cover of the book up six feet by ten feet and hung it outside the gallery. A massive Memento Mori, fulfilling the purpose of the cover, why I requested it, in huge, bold, glaring clarity. An amazing sight, to walk down a Mile End street to see your book's skull looming in the distance.

On Test Centre

The remarkable activities of Test Centre as a publishing house over the last year are unmissable to anyone who has got their ear to the ground in interesting poetry in the UK. & being in London, what they have achieved, to become synonymous with some of the city's most vital and brilliant authors from the last few generations past, while in fact being very much my generation, our time, utterly contemporary, is really a credit to them. More than that they have done this, won the respect of readers and writers alike, because, like the work they publish, they are discerning, considered and innovative without pretension. They have a singular aesthetic too, one that captures the best of the East of this city in the 21st century. Again no mean feat.

Having seen their publications of Iain Sinclair, Oli Hazzard, Derek Jarman, Stewart Home and others, I feel very fortunate to be beginning a relationship with them in 2015, one that already feels deeply collaborative and full blooded. They will do great things for my book {Enthusiasm}, which I believe strongly in as a collection. It is singular in focus in the way that my other works are, yet the subject of that singularity is elusive. That's what I've been trying to achieve for sometime, something that leaves the trace of cohesive precisely because of its ambiguity. Its a collection about style too I suppose.

You can read a sample of poems from the collection here:

The Quietus http://thequietus.com/articles/14302-two-poems-by-sj-fowler

Gorse magazine: issue 1 http://gorse.ie/issue/no-1/

The Morning Star http://www.morningstaronline.co.uk/a-c7e1-SJ-Fowler-The-bleached-is-not-a-white

Stoke Newington Literary Festival - June 5th 2015

Just a few days after the launch of {Enthusiasm}, I had the privilege to read alongside Iain Sinclair and Tom Chivers at the Stoke Newington Literary Festival. Influx press, whom I respect immensely, had been given a day to curate and had invited Test Centre to present three of their authors. So I had the pleasure to read alongside two people who have helped me greatly in my work. Iain was the first to really support my work, extremely early on, months into writing, and Tom has been a consistent champion of my stuff. At certain moments, certain perceptions and realities only become real because you hear them being made so. What Iain said in his slot, about my work, will stay with me as a great treasure for a very long time.

The very first reading from {Enthusiasm}

A six by eight foot billboard hung outside X Marks the Bokship at Matt's Gallery, Mile End, London. The image, the cover of SJ Fowler's 2015 poetry collection {Enthusiasm} published by Test Centre. http://testcentre.org.uk/product/enth...

The video, shot by Jess Chandler, features Fowler reading in front of the billboard, on a ladder. The recording, made in the The Cast of the Crystal Set recording space, curated by Eleanor Vonne Brown, features an assortment of poems from the eponymous collection.http://bokship.org/xaudio.html

How I Did It: ‘The Interrupters’ my article for The Poetry School - July 2015

http://campus.poetryschool.com/how-i-did-it-the-interrupters/ An intriguing series from the Poetry School, hosted on their Campus platform, where they ask poets to discuss the process of writing a specific poem of theirs. Some previous editions were really interesting, but more often than not made me realise how different my process can be from the norm. So this article, where I discuss my poem The Interrupters from my recent collection {Enthusiasm} published by Test Centre, is an attempt to honour the article's remit but still maintain a true reflection of my actual methodology.

"This poem is part of my {Enthusiasm} collection, recently published by Test Centre press in June 2015. This was one of the last poems that made up the book, all of which were written while closely reading a few poets, over perhaps a five or six month period of writing for hours a day (mainly due to my employment giving me time to do so ((not literally)) and having crumpled photocopies of poems in my back pocket to read as I wrote). Way over a hundred poems were written, then in late January 2013 I culled most and left the rest for a year to percolate. Then I made an edit (all in a word doc). Six months later, 18 months after their writing I edited them again over two weeks in the Shetlands Isles, before sending that version of the poems to Test Centre. The poem has stayed pretty much as I wrote it initially, and I tend to do my edits while typing up what is written in my notebook. In this case, with this poem being unusually clear, neat and well formed, this didn’t seem necessary.

I suppose each collection I have published has been an attempt to relate a style, or form, or concept, to a subject. Not the other way round. No collecting has been done after the fact, the fact has been established and then the collecting. My process is one toward a changing ideal. I don’t denigrate those who are consistent, or whose evolution is subtle, but I personally find the notion of radical growth, or variance, to be something I aspire to. It comforts me that my work is different book to book, that I produce things that bear not a singular stamp of my authorial ‘voice’, for I find that idea unrepresentative of my experience of being. It is not a metaphor to say we contain a multiplicity. I am a different person depending on my mood, my company, my job… As such I am a different poet, I have a different voice when writing about boxing than I do when writing about prisons, or when I’m using collage technique as opposed to visual poetry. And most especially when I’m writing mostly at night, as opposed to the morning, or when I’m reading mostly one poet as opposed to another.

The point I am trying to make is that this poem is, and this whole book, now represents to me perhaps the most enjoyable result of a period of writing that was also a period of my life. One past, but when I read this poem, that has the briefest fragment of trace remaining, literally now marked onto a page."

Richard Marshall reviews {Enthusiasm} on 3am magazine (23-12-15)

A really discerning review, one that roots my work in the world and gets to the heart of of much of my purpose. I have (or try to have) an ambivalent relationship to reviews, but then reviews are different from criticism. None the less the nature of my work means that I always feel lucky when someone seems to connect with it, let alone extrapolate what Richard Marshall has here. I can't pretend it's not enlivening, that it doesn't fill me with optimism, to read how clearly and incisively he's recognised the purpose and philosophical context of much of what I'm trying to do, especially in {Enthusiasm}. http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/enthusiasm-review/

{The pictures below are my own, from various travels over the last year, a way of repositioning this text as a new thing in this new space.}

‘How does fertiliser help the bomb?’ Fowler’s ripe question.

Ask what, or who, where, time, city, rural encampment, rubble shack, the evaluation at the abyss or in the long run, sans calculation, algebra, logical filigree, ask what epistemic holy ghosts hissing like a hot philosophical lava miniaturise with poetry. So starts Fowler’s new collection, a ‘golden horde of disabled will’ where the clues ask around for what might be tagged a surveillance of change – change of mind, heart, feeling, rationality, calculation, then gadget technologies dressed as learned prim theologies of rationality, or other kinds of monkey stuff. What’s the fertilizer, we ask? What the shit? TS Eliot produced the ur-poetic gadget for digging it out and spreading it, raiding Frazier’s junk anthropology for faux metaphysic slurries, shimmering it around so the muck eventually calibrated different degrees of an idealization where limit of memory, history, psychological backdrops, sheer physical stamina in the pen, camera, digital peg, imagination, future, hope were disguised and rendered a ‘Wasteland’. This ability to make material idealise into something transcending our actual epistemic situation fools some into thinking we actually have transcended it, suggesting there is some metaphysical substance holding the fall of words and thoughts to account, epistemic holy ghosts hissing like a furnace baked philosophical depth bomb.

Fowler’s too wise to make that mistake. He works in the limits of what he calls, as an abbreviation for the complexities, ‘enthusiasm.’ Of course there’s not a single proposition attached to that label. But it is something ‘not limited by anything & the imagination of flight is apparently a mild head cold to the viral germ warfare we ought suddenly employ when thinking about what we might do with our future time…’. That is the ultimate focus. No summarized norms, epistemic stances calibrated to measure the dreamed metaphysical ghouls, maybe even harness them, or drive a stake through to a heart, or a yacht to navigate territories. ‘Water/ doesn’t need a boat you arrogant fuck.’

Fowler works in the line of poetics that sees poetry as a way of changing its reader perhaps first put out in 1751 by Sam Johnson in ‘The Rambler’ where he writes of ‘the Force of Poetry’ being able to change and shape its readers. Pound writes of poetry’s rhythms being ‘forced onto the voice’ of reader’s speech. W.S. Graham, who haunts this collection as a lost poetic daemon, wrote in 1946 about a ‘poetry of Release’ which makes ‘the readers change.’ What Fowler is doing, it seems to me at least, is evoking a readership, seeing poetry as an activation in living and an intersubjectivity in reading. All sorts of things tug at this idea. JS Mill wrote of poetry being something overheard in contrast to being heard, a view resulting in the private vector of its influence;

‘ … the peculiarity of poetry appears to us to lie in the poet’s utter unconsciousness of a listener. Poetry is feeling confessing itself to itself in moments of solitude.’

Well there’s something valuable in this. Fowler’s war poetry – I’m labeling it thus just to exaggerate a point – can be read as ‘apostrophes directed elsewhere’, to use Coleridge’s useful phrase, to emphasise that Fowler’s poetry protects poetry’s special value, & is much much more than mere propaganda. Yeats as always helps: Fowler is assuredly quarreling with himself not others in this. Yet his imaginative links are nevertheless public too, as public as Whitman’s ‘Leaves of Grass’ or Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and if Mill helps there’s always the fear the definition pushes poetry further into the unheard margins. His poems require more from us than brooding reflection and mute feelings in domestic solitude. There’s a somatic demand: poetry urging us to rewire body and nervous systems as well. The disturbances of syntax and unexpected diction are ‘political engagements with consciousness’ to bring about the ‘making of the reader.’ And it’s not a one way street. As Auden writes in his Yeats elegy; the words of poets are‘ … modified in the guts of the living.’

Art writing – and Fowler’s is definitely that if it’s anything – as a response to war is not an obvious move these days. Yet art is natural– everyone can without help talk about how things seem to them, and because of that, everyone should be able to do so as well. Alva Noe makes this point vividly. The art sense is like nipples on a man: useless but universal. Forever we’ve been creatures with language, dress, pictures, technology – and art. Art presupposes technologies of doing. Choreographers presuppose dancing but aren’t dancers. Poets presuppose language – both spoken and written. But they aren’t speaking or writing. They are showing us speaking and writing. They can startle us out of complacent acquiescence, make us see, perhaps for the first time, what we are saying and writing and reading, what is sayable and unsayable, and work into the foreground what we leave back in the background, and so change our minds, help us think what hasn’t been thought before, or remind us of what is hidden by what we do think, what we do say, write – and also what we read and don’t read, and how we read and don’t read. Art is the space that requires minds to critique, so criticism becomes something essential too, and no contingent journo sideshow.

What’s Fowler writing out of? He’s responding to other poets, others writers, other artists, audiences, teachers and students. He’s responding to journalists accounting for the wars abroad, the pieces here there and everywhere, the news bites and the elongated discursive pieces, the mediated event stuff that our hyper-technologies of propaganda, information, opinion etc etc churn out minute by minute. And finally he’s listening in to the conversations that are happening all over the place about all of this. His art is its own problem because it is itself a critical practice. Fowler is removing the discursive pieces about war from their settings. From his angle they become strange. His poems are, to use Noe’s fecund term, a ‘strange tool, an alien implement.’ With this tool we investigate ourselves. First order activity – talking about wars, inequality, the environment etc etc – organizes us. Art (and philosophy) takes these activities and builds a space for us to examine ourselves doing these things. And then the activity of art loops back (again this is the terminology of Noe) and reorganizes the first order activity. Our free, untutored activity of war talk and the rest has now been represented and so becomes shaped by the critique. And then this new, shapely talk becomes subjected to more art critique. And this in turn is looped back. It never ends.

This theory of the aestheticisation of writing changes some assumptions that commonly hang around. One common assumption is that writing is the recording of speech. But it wasn’t. It was originally a technology of scoring, for the purpose of counting. ‘The first writers were bookkeepers and they wrote not to represent their speech or talk about goats or bushels but to keep track of goats and bushels…’ This means speaking or writing: it’s an open question which came first. There are graphical practices at least as old as linguistic practices. Writing however does record speech but it comes from our need to keep track of what is being said. Writing was a score card, tracking the first order practice of talk. Of course it has been looped so many times now there’s no way of knowing where writing and speaking begin and end. Art makes poetic technologies so we can interrogate language practices. Fowler is working his poetic gadgets to display our linguistic discourses of war in the new context of now. The frenzy and mix, his measured risk taking, the shamanistic self-outcasting invokes a dream world where we’re invited to crawl along and out of our now remote intimacies. Other voices enter his sequences and help curate his protean strangers: Brian Catlin of ‘The Stumbling Block’, Iain Sinclair, Allen Ginsberg, Gavin Jones, Allan Moore, Stewart Home, Laura Oldfield Ford, Kathy Acker, Paul Holman, JH Prynne of ‘Tortrix:

‘This skin river was directly marked/Its tracks to l’esprit fou, for the second eye-opener. A new bite at his instep/is corrosive and colloidal at one throw’ catching the same sheen as Fowler’s ‘the City’:

‘always a beloved space of trans. To accept what is/greed n pets not so much in reasons/for the closed will open in matters of delicate urgency/for a winter bonus to claim his prescience/because bark numbers anyway/suicide was induced by/with octopus limbs and no teeth…’ etc.

Reading this collection in the context of terrorist threats, Syria, the inequality class wars, domestic hells, all the nightmares roosting, what we realize is that Fowler is our war poet, breeding his lilacs out of the blood soaked April ground of current history:

‘should I begin as if it were a story for in (not during wartime)/ they mistook a story for a poem as often as/I’m not saying you never had it so good/but that is a fact , isn’t it?’.

He’s grappling with the extreme consciousness of these mediated discharges of extreme violence, the weird collision of mutable elements of the everyday with an excessive, unavoidable degradation of sensibility constantly bombarded by violence and names of violence and symbols of violence and effects of violence and rumours, denials, gratuitous, unclear, unclean of such. ‘You’ve never had it so good…’ is where the war starts, and places the reader squarely there, ‘in’ not ‘during’. If taboos are a way of vanquishing violence from the everyday then our contemporary context is where taboos are being reversed. Fowler mixes actor and costume, mask and dance, plays choric master to the Dionysia of this reversal , is a voiced chorus of phallic tragedy played across the broken-hipped syntax of polyphonic marginal identities.

‘ how long would you like to fight? You pick the term/ for we are not under bombing we are facing it/what is feared is a story that explains itself/ so much it almost isn’t there upon its ed/the helicopter gun that’s known as birth control.’

This is chorus intruding the action, standing at the centre which years ago didn’t hold but imploded. So the fragmentary, uncentred is everywhere. It’s an ironic usage, ‘ prepared like a kidsaw in a cat’s paw/ happy hinged to lift a black eye..’, with domestic violence and domestic pressure nose to nose with helicopters and bombs somewhere else, but intimately ours nevertheless, addressed simply and partially as it disappears from view in the poem ‘done the line’ for example or ‘Black Eye’, for instance, an experiment as notable as Racine’s ‘Esther’ or Goethe’s ‘Faust II’. What’s the reason for saying there’s a chorus element here? Throughout the sequence there’s an interplay between actor speech and what, loosely, I’m thinking of as a chorus with richer imagery contrasting with the movement preceding. There’s often a pairing of actor voice and choral in the same broken-backed line, so we have ‘I have been to prison and patted down on the way in this sorry event…’ which then is infused with the chorus ‘…my being birth well blue/truffling up the treegrove…’ which seems to abandon its dramatic identity just for that moment before returning it, ‘… I missed my pet/>my training partners> friends>family>wife>children..’ and then letting go again to the margin where images crank up once more, ‘… who in the night were snowly peaks…’ This is interesting because the use of the chorus died out when private subject matter replaced the public. Fowler’s versatility is partly his recognition that the private and the public infiltrate themselves more than ever before, that we’re both bombarded with news of other’s lives whilst channelling private echo chambers of solipsistic narcissism.

‘No two can meet the way we have met’ is a quote from WS Graham that slides into this wild doubling space we now inhabit and in the poem ‘the Interrupters’ Fowler ventriloquises an analytical voice;

‘… this is how violence starts, first/the perception of a slight of an insult/within the context of a culture that/ has taught the imperative that you must/never back down. Second the decision/ that the affront can only be answered/in a physical reprisal. So death ensues.’

The ‘slight of an insult’ plays with the notion of the curtal, shrinking to prize a harmony , complication and overcomplication – so ‘slight’ becomes both something smaller than it is and the letter-longer, so larger, ‘sleight’, itself a sleight-of-hand creating the illusion of unity when in reality there’s nothing but multiplicity and cunning paradox. Hopkins would have been proud of this moment. Elizabeth Bishop played all day with curtal double sonnets and Fowler plays to the extended miniaturized sonnet cut in half and then divided again by a randomizer. His extreme use of syncope can find the textures it needs, cutting up huge passages to remove excess but its less brash here than in earlier collections. Yet his gathering everything all together is refined almost to a secret: some objects are displayed out of its material or consequence: ‘a man’s device for private rooms and the happy /distance between rich and poor was as it is…’ stands in for the award nomination of ‘… the furry royal pardon vest.’ Fowler has learnt the Martian high jinks but integrated them so well that they don’t advertise themselves but are subliminal, and nothing is anything unless it overlaps. As always his use of synecdoche can depend on how it’s interpreted, whether it’s expected, and links with Hobbes: ‘ a multitude of men are made one person,’ and also links with anthropological studies where it mediates between different groups in a social structure, & species and genera found in nature. It’s a trope banded about when environmentalists and business interests do battle, and that’s another battlefield Fowler is writing towards, like Bruce Chatwin done by Werner Herzog:

‘aboriginal prisoners of war are allowed/ their kangaroo tail delicacies even if they/ have been tried by white courts…. Here in the desert, where snakes have need of/their horrific poison, lest they starve.’

Fowler’s imagination inverts: his erotic convulsions are deathly, the urges of the flesh become decent and induce final feelings of nausea and piety: ‘ two quiet high points in space shuffling/rivaling the tory in the actual event…’ Pity is ‘gutted’: well, here again we see Fowler at play. Pity can be a matter of being gutted at a push perhaps, but here it’s refined out to something savage and self-aware enough to wobble to a hotel , a wall, ‘pre-penicillin/wars with crows cawing in the forests…’ in a poem; ‘…. This poem that I had dreamed oh well/on with the end of the german basics/the lean to a spider you are afraid to become…’ which catches the wry desolation of the poet facing the need for epic afterlife and finding there’s nothing to build it from but rubble. Without the ‘perfect line’ the poet recognizes that ‘not going very well’ is what has to be bred here. One of the needs in this writing is a reader who works to change the habits of minds that are ‘… wealthiest/a sort of pale, friendless mercenary, so equipped to deal with irascible children & a frightening lack of perspective…’ which is as good a summary of the culture at the present that I’ve read for some time. Our times seem to be led by ‘pale, friendless mercenary’ minds and in response Fowler hovers between answering back with blunt nettled spirit or else intoning half baked charms, spells that hint at secret cults, liturgies, hymns, folded into atonements rinsing the mind of their bleaching, desert attachments.

That the mind holds to illusions, that we are able to function as if there’s no horror happening just over the horizon, or even in the same room, is something that Fowler is drawn to again and again. The suffering that grows so deep you can’t bear to pay, though pay you must, is a central theme, and a conceit that makes his war poems resonate with a felt truth about our special kind of modern warfare, for our wars reveal ‘… the possibilities /of the human mind to pretend everything is fine.’ In a particularly subtle physicality his poem ‘the bleached is not a white’ takes the death of a whale as a way of showing the heartbreaking route away from civilization we’ve taken, a place that’s as public and as private as can be, a narrow road to the interior that is literally broken up:

‘… as it perishes it’s heart bursting in attack, the salt/ water damning its arteries, the whale turns eyes down/ to watch its deathplace rise into view…’.

There’s a marvelous, deadly, hard-won simplicity and directness in this that can evoke the physicality of his spiritual journey, a kind of Zen mixed with highest art, Basho’s journey to Oku recalibrated as allegoric caustic satire. He also evokes the elisions we remember from Emily Dickinson, perhaps her ‘a bird came down the walk’, as well as cumming’s ‘since feeling is first’ so like a child, like a foreigner, a joker, he plays, compares, couples, contrasts, double arranges, jams semantic enquiry into fragments, anti-paradigms, colloquial, dialectical, vulgar, irregular arrangements that seem to forget what they started or else never intended a main clause to have any fina closing heft, which after a while may be taken to be a political stance. In this at times he is Beelzebub in Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ who refuses the conventional obligations to honour what he starts with a completion, ie; ‘ If thou beest he; But oh how falln, how changed/From him…’ Milton wrote to confound the poetasters of his day who would put together edifying verse for educative reasons: he deliberately wrote so that his poetry could not be easily chopped into such squeamish morsels. We’re reminded of Dylan here: whatever they’re up to, ‘its not wallpaper.’ Shelley moved towards the impenetrable, shifting expectations by removing closure commas, staying on the side of grammar but posing something unacceptable to the reader not wanting to think recursively.

‘The extreme hope, the loveliest and the last,/The bloom, whose petals nipped before they blew/Died on the promise of the fruit, is waste.’

Shelley is asking the reader to puzzle with him, and reminds us again that language isn’t always, nor essentially, communication, but keeping a difficult score.

So too the poems track dark nights of the soul where if we’re lucky it’s ‘the smaller death drive today, a near tendency’ and that nearness is the key, as if Fowler is drawing everything from a distance into a circle of reach, his ‘close shaves’ are those at hand and the dark enchantments he extracts are ways of bringing everything, no matter how huge and distant into his circle of intent. If anyone can restore the price of the stumbling block to poetry then Fowler, devouring whole the evil spirits in his figures and tropes, is our best last bet. An abbreviated tour of this road trip reveals the considered will of his haunted poems, the spectral momentum that comes with the names of animals and the numerous maledictions of children and child birth, as if birth was the fault and the gift immersed in the primal, maledicted horror of poetry’s elemental violence.

Our blind activities are overheard as chunks of patter in a public space. It’s like we get what Bruno Ganz’s angel in ‘Wings of Desire’ hears before he resigns himself to the voracity of the human: ‘… painted pink dips, the day of the dead… liver fluke packing ready bags…not born children… elicited sympathy… apart growing closer slower… frosted grass.. the recent meat… non-homo… empty space… new towns like Swindon… off limits… water rats… bear traps… salmon… ghosts of the civil dead… cut bone and cocktails… deaf dolphins… my human skull… cat’s paw… prison… Vietnam doubt/death/debt, bleeding nose and raw potato… comets… a lost jelly eye… your own regret/in gardens… further nosebleeds… vigilante justice… auditioning in szerz/with michelle wilde… born again, born again… the eyes of children… cutting off people’s heads… the venus nebula/is ever expanding… the gypsy wound… a tomb of trinkets… a baby dies in Bristol (if)… thinly veiled my dog is on the fellows… a baby is cruel… muslim.. is a hard hunter… eats the bed… god himself before social services let him down… Cristy’s clit… morals not changed from 2013 years ago in the middle eastern desert… baby mutu… the baby of the north… an alcoholic, unemployed + eating the fatty foods like chops… not good news, not good + abortion… choosing between money and life… the English longbaby made chain/mail redundant… baby men have always had murderers + mistresses… baby in the bath… baby bullet… bad parenting where the baby grows up to be a duck… baby bowie… she runs where once she crawled… a baby being made in the oven… a shoal of baby Orcas… butter my brother says/is very tatty… she’s descended/from sunflowers which is a bath of balls… death throes is not a dance… as ephemeral as it is a colon is not a delusion… day of the dead parade sober… figure hush in the crib… saw to Ealing as a planet earth… a Tetris elephant… the butt of an Angolan rifle smashed the natural eye from his head… older/in the last white sun… horsepower colonies… a filial son, how long would you like to fight? You pick your terms… weeping & smiling fits of those still asleep… Kaspars still dead is missing strings… a victimless act of catharsis… I have not killed a day so small… his black dolphin… spectre of miniature women… a nightmare about a millipede /with pistons… I sniffed the crotch the other girl soiled her underwear… the doctor stands by/fondling the crease… a sheep floats, is all but eight months old, into a black rubber bag… ancient karian on a bier east greek strictly frontal stance… quarter naked who dwarf… my prostation at gunpoint/& a small one… the rains of Castemere… Tatar. tamerline eats babies… slug trails… the will fall blinded…’ These voices convulse with disclosures that come from what is left behind, or is destiny, or a hiding for nothing. Fowler catches the protean energies that tune our sentiments and reasons: he’s showing us the decomposed contagions of our lively souls, their desire to touch and be touched without pacification.

Every weeknight I’m at Paddington Station in London. There are always crowds. All over there are working Greeks, Pakistanis, Indians, Afro Caribbeans, Turks, Irish, English, Welsh, Spanish, Portugese, Italians, French, Nigerians, Poles, Ukraineans, Chinese, Japanese, Taiwanese, Australians, Americans, Arabs, Jews, Muslims, Chrsitains, atheists, Hindus, Rastas oh the whole lot, all there waiting for trains or moving away to the underground or taxi ranks or the streets, or serving/buying/eating hot dishes from kiosks, or browsing temporarily inside the shops, or working on the lines, or tapping on their mobiles, or waiting, having a smoke, moving or rooted for a moment, or preening, or letting themselves go and all of them superior to the life being lived, closer to illumination than the notch of mere recorded conscience, caught between living and history’s noises unfolding outside in the super lucidity of exhausting, quivering liveliness. It’s a holy secular place of penetrable force, a huge disorder of facts where alchemies of existence take place every day like we’re all bubbling up inside an immense kettle or melting pot. No matter that death and the butcher’s eye is always haunting it, this immediate and apparent reality of facts, this bodily, physical blossoming of anonymous people under the vast glassy dome of the station’s insane confabulation is delicate precious, of immeasurable value like the poet’s spirit ghosts of deer. Yet it’s a secret. Fowler’s voice brings us this news of ourselves, resonates with this intelligence, and discharges the sentiment without sentimentality, unafraid to find the perspective that can recall the protean charge of our insanely complex contemporary existential veils.

Artaud summarises this in his detonating comment on Van Gogh: he talks about a sensibility that arrives;

‘ … where thinking is no longer exhausting,

and no longer exists

and where the only thing is to gather bodies ….’