https://richmix.org.uk/raised-rich-mix-interview-with-european-poetry-festivals-steven-fowler/

Some selected questions below, please click the link for the full interview…

In this Raised at Rich Mix interview we caught up with long-time Rich Mix collaborator Steven Fowler, who is founder and director of the European Poetry Festival.

While it’s difficult to know how to proceed in these times, if you’re turning to creative pursuits, we think Steven’s interview might help you focus your energies.

Steven is a writer, poet, performer, playwright, artist, curator (yes, he sheds some light on how he manages to juggle all of those talents at once!), and has been a part of Rich Mix’s fabric for ten years. His enthusiasm for creativity in so many forms is a good reminder that we all start somewhere with our creative practices (if we have them), and that there’s no need to be put off from trying – especially now.

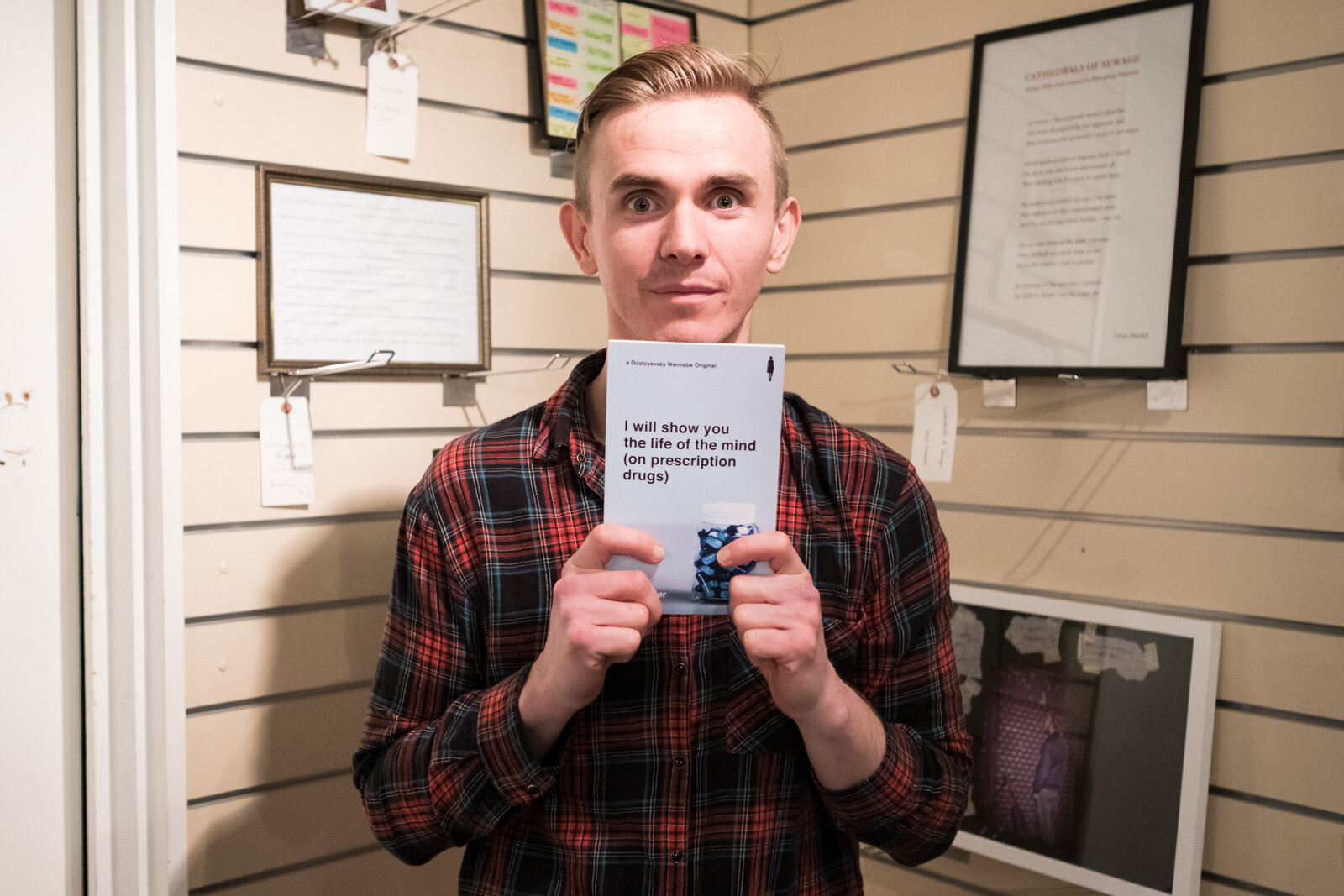

If you’re yet to come across his work, use his words below as your introduction, before taking his new book I Will Show You The Life Of The Mind (on prescription drugs) for a whirl, which recently launched at Rich Mix.

RM: What motivates you each day to continue to write? Do you find yourself turning to anything specific if you’re ever feeling demotivated?

SF: My work is remarkably unpopular and uncommercial because I have worked hard to have the conditions of complete creative freedom, within reasonable limits. In this reality I am profoundly aware of how pointless my work is in all ways but for myself. I enjoy doing it, I do it for me, it’s a way of exploring existence and doing a job which isn’t depressing or dangerous. If other people get something from it, amazing! That’s magic. But a bonus, one I wouldn’t expect. I wouldn’t assume to know what makes others happy or interested. So I’ve no need to get motivated, I’m always writing because I like to do it.

RM: What’s something very few people understand about poetry (or spoken word)?

SF: Maybe that these two things are really different in my opinion. To me, poetry is rooted in the fundamentally unbelievable fact of language itself. How is it we are able to communicate through grunts and marks? And how is it we are unable to capture the sensation of feeling and thought within us in language? Wonderous and mysterious. My work is then in the tradition, from Heraclitus on, of making things more strange in poems than reality itself. Not less than daily life, but more. Paradoxically this makes some people, who consider things in their actual complexity (because existence is complex whether we want it to be or not) feel more at home.

RM: If you were living a parallel life in another universe, what different talent would you have pursued?

SF: Martial arts or maybe a military career.

RM: You work across an impressive array of art forms – how do you decide which ones to focus your time on?

SF: Acknowledging I am being really reductive, I use a kind of simple matrix when teaching which might answer this. Method / Subject / Reason. The first is technique, which one to use, (sound, film, poem, fiction, book, live etc…) for the second one, what am I interested in, what is the thing I am making about? And third, exploring why I want to do either of those things? Somehow, instinctually, I try to find my way into the right forms for each thing I get to do. A lot of the time, happily, it’s due to the specific constraints, the context, of the publisher, venue, commission etc… Other times I feel like, say my interest in disappearing West London, is best done as a film rather than a non-fiction book.

RM: Do you see a thread that combines all of your work? An overriding purpose or mission? Or do you spend a few years immersed in a number of themes, before moving on to the next?

SF: I think about this a lot, thanks for the great question. I want to reserve the right to explore whatever I want to, whatever subject, even if its banal, alongside what others think is more ‘important’. But overall there is something underpinning everything I do. I never want to patronise people; I never want to tell them what to think and I want to embrace the actual complexity and difficulty of existing. I don’t want my work to be a shadow version of experience, a lessening of experience and ideas. I want it to know its less and then be free to be something new.

I think all art is supposed to be a place for the parts of us, of our lives and thoughts and being, which have to be suppressed in the required and sensible everyday interactions of work and relationships and friendships. It can please or challenge, that’s secondary, but for me, it should connect to that which isn’t easily knowable and maybe can’t be known. This sounds stupid I think but this is under everything I do.

This is more important than pleasing people and being popular, because that isn’t hard to do if one is cynical or if one is not thinking deeply about what it is we are all doing. Morality, for example, is very easy to peddle. It used to be the territory of religion, but seems to be in art and poetry much more now than even a few years ago.

RM: You have worked with an amazingly broad range of themes – from neuroaesthetics, mortality and linguistics to collaboration, fight sports, prisons and bears. Tell us about a topic you’d like to bring into your work in the future – what fascinates you now?

SF: I’ve just released a book about the prescription drugs epidemic and the human mind. It’s a choose your own adventure poetry fiction collection. But this book is done! I’ve got other books on the go on other things, some coming out this year, some next, working on them as we speak. A book of long poems about Apes, The Great Apes. A poetry collection on surveillance, That Which Don’t Concern You. A book of prose poems on smells and scents, The Parts of the Body That Stink. A novella on museums, as I worked in the British Museum for seven loooong years, M U E U M. A new series of publications each exploring a different poetic method – Concrete Poems, Photo Poems, Maths Poems… And in July, my next book is called Crayon Poems with Penteract press, all poems made with crayons!