ANIMAL DRUMS | Feature length Film

A film by Joshua Alexander and SJ Fowler - Running time : 76 minutes / 2019

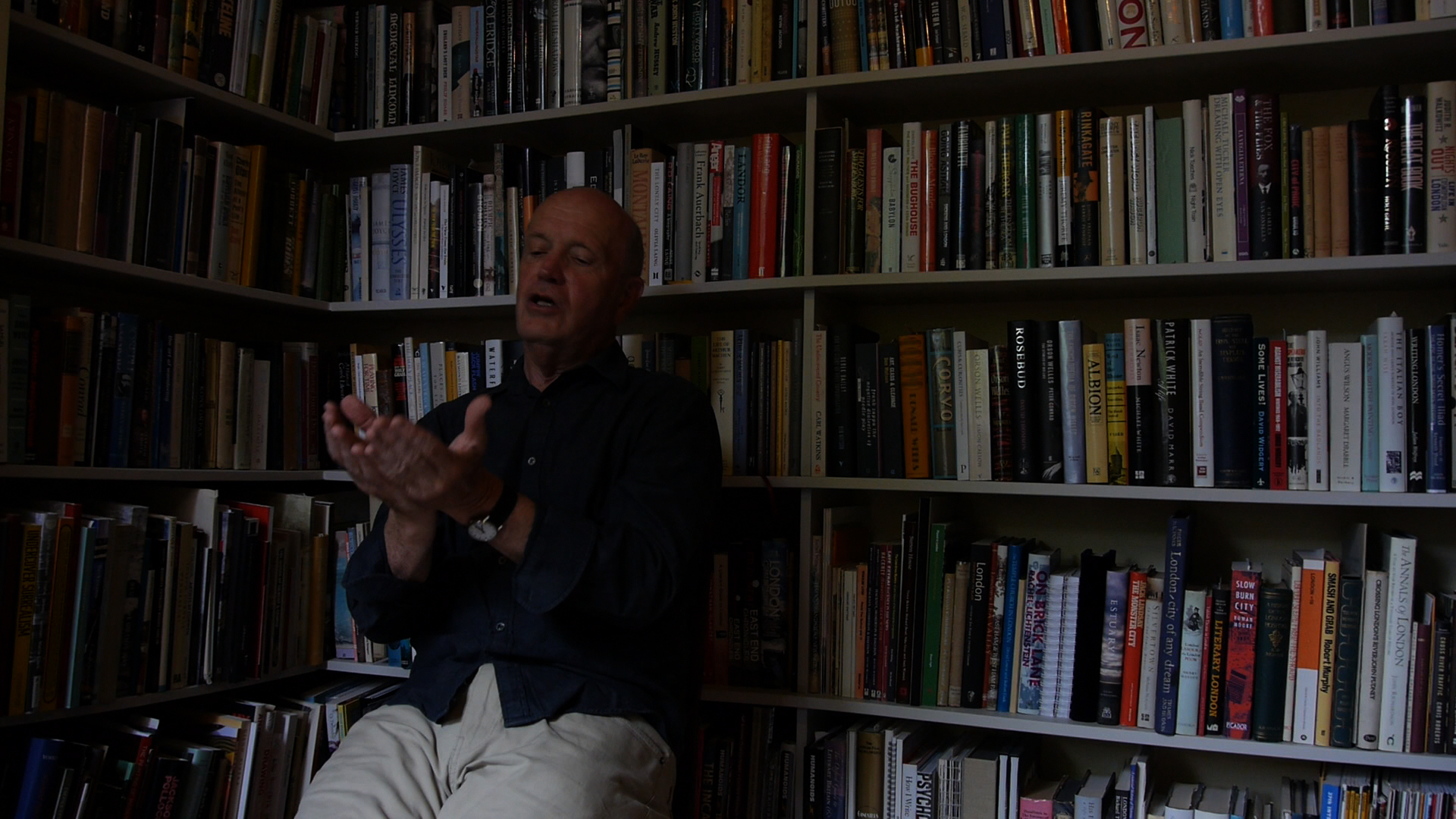

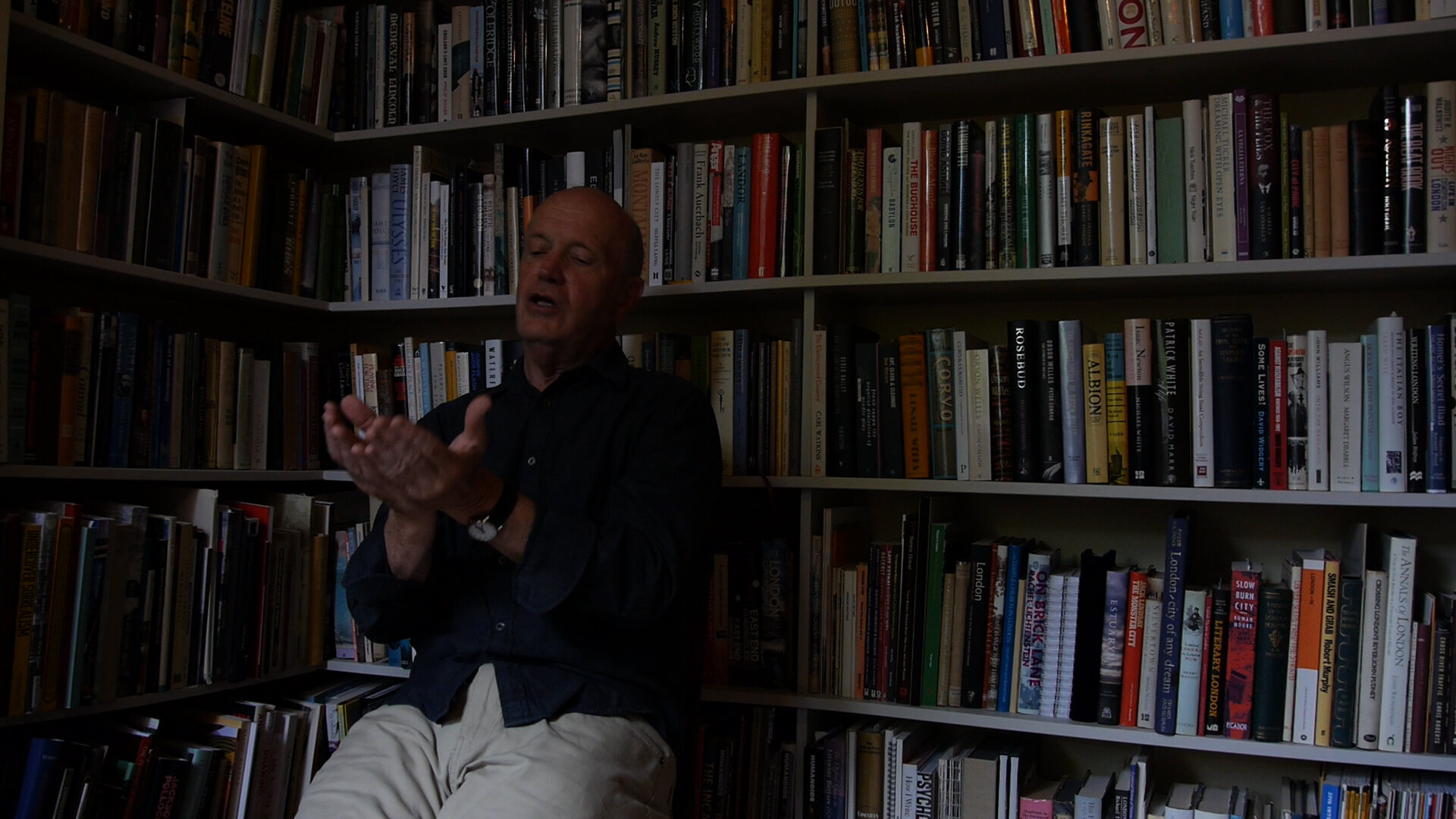

Featuring Steven J Fowler, Stewart Home, Iain Sinclair, Lotje Sodderland, Simon Christian, Edie Deffebach, Andrew Breaks, Stuart Westerby

The first significant feature length poetry film of the 21st century - Gareth Evans

An essay review of The Animal Drums by poet and critic David Spittle on Hotel Magazine https://partisanhotel.co.uk/After-Animal-Drums

An introduction to the film and a poem from the film, also on Hotel Magazine https://partisanhotel.co.uk/Animal-Drums

Iain Sinclair’s poem-text responding to The Animal Drums, read at the Whitechapel Gallery premiere, published as audio on the Tyrant Hotel audio magazine http://magazine.nytyrant.com/tyrant-hotel-mother-pig-opposing-disneyland/

An interview which discusses The Animal Drums as part of The Light Glyphs series https://www.dspittle.com/single-post/2019/07/22/8-Light-Glyphs-Steve-Fowler

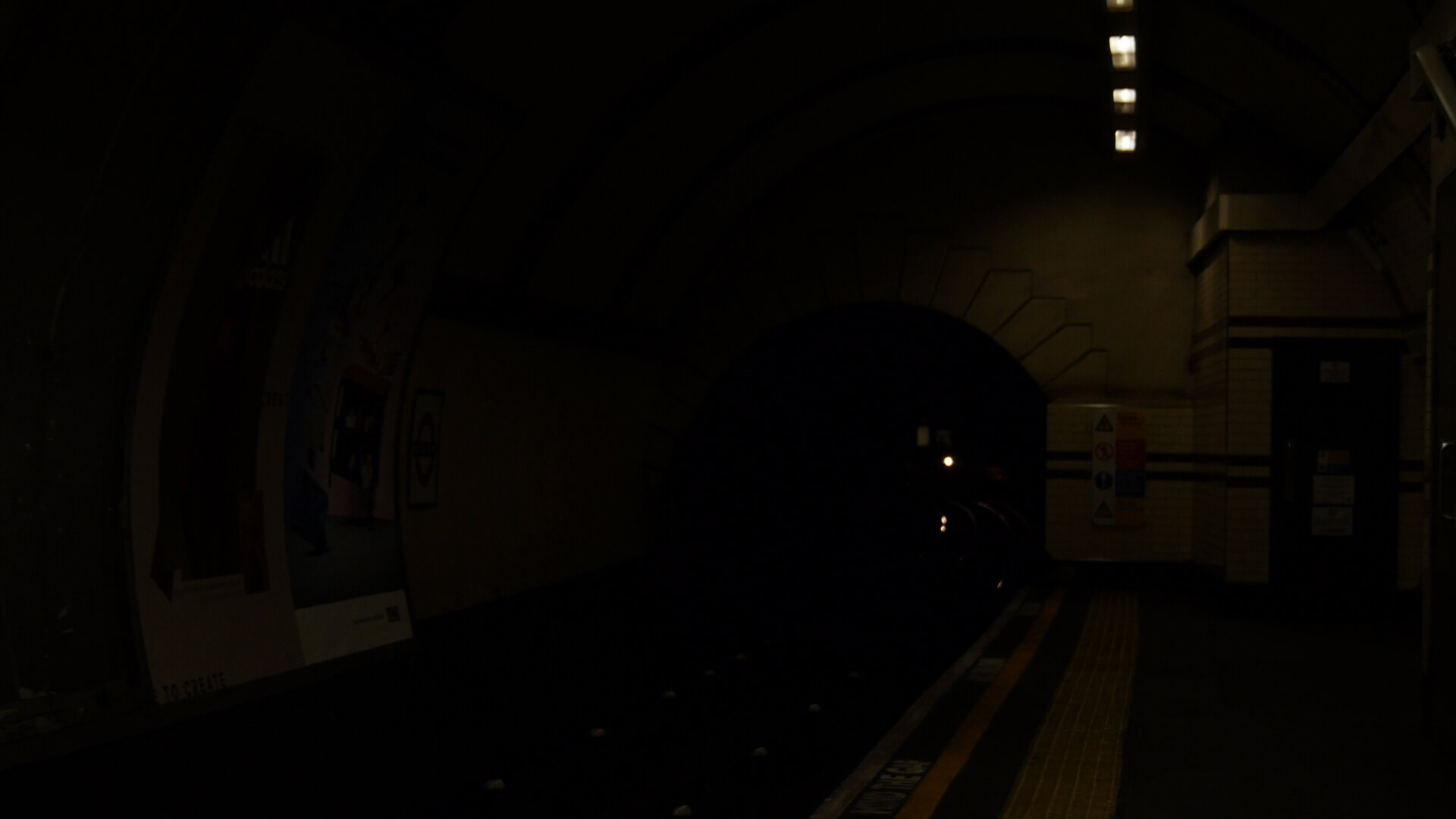

The Animal Drums is an attempt to create a distinctly poetic film, in feature length, that explores the sad, macabre, abstract threat of a contemporary London in the grips of constant and nefarious growth. The film charts the the particular, baffled and morbid character of English attitudes to mortality, along with the specific influence of place and conformity on the quintessentially English deferral of emotion and melodrama. It captures the ambiguous menace of an often accidentally humorous resolve, manner, apology and understatement so prevalent in the English character within a city that is proudly unlike the rest of the country, and it dwells upon the unfortunate consequence of blind development. London disappears under the ground of the film’s ambiguous protagonist, who is half victim, half perpetrator. Gently mad, positively lost, we follow our host through the bounds of a changing, money-washed capital city.

Recalling the tableu film-making of Peter Greenaway and the lyrical disjunction of Harold Pinters writing, Gareth Evans suggested The Animals Drums as the first significant feature length filmpoem of the 21st century, in the tradition of Andrew Kötting and Patrick Keillor. Featuring a fusion of documentary technique, montage and theatrical set pieces, and featuring appearances from authors like Iain Sinclair and Stewart Home, alongside actors and non-actors, The Animal Drums is unique representation of modern London in old England.

The film was shot from 2014 to 2019. It was made with constant revisions around its method, deliberately aiming to fuse poetry, improvised speech and the language arts with film grammar and the possibilities of film editing. Multiple new texts were written to drive the film, many of them distinctly poems.

The film was premiered at Whitechapel Gallery and then screened at a select group of cinemas in the UK, including Oxford’s Ultimate Picture Palace. https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/events/joshua-alexander-steven-j-fowler-animal-drums/

Audio from the Whitechapel Gallery Screening with Iain Sinclair, Gareth Evans, SJ Fowler and Joshua Alexander >>>

—————————————

David Spittle has written a critical response to the film, published by Partisan Hotel magazine https://partisanhotel.co.uk/After-Animal-Drums

”The glitching pulp of red that begins the film keeps flashing across in other sequences, a blinked glimpse of the plague doctor and occasionally a peaceful but disintegrating shot of a forest. These images become like obsessive thoughts or the rupturing of flashbacks…it is half way through the film that we realise the incoherent red glitch is a distortion of a figure about to read, a performance. Steve Fowler has often looked at ways to unsettle, include or challenge audiences in order to resurrect the polite coma of most poetry readings into an unpredictable exchange between people. But it is that space, the reading—and more significantly, the performance—that seems to encapsulate a locus of anxiety for the film: a moment where the personal and persona of what might constitute Steve Fowler is allowed to blur and seem vulnerable. He mutters into the microphone, ‘It’s funny, people have all these thoughts in their mind and you speak to them…’ he trails off, repeats and trails back, as if lost and even afraid. This is followed by the admission, ‘I have a problem with impulse control’, which is then repeated around four times before descending into an apologetic mantra: ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry…’For the film, it is unclear whether this is the protagonist (that both is and isn’t Steve Fowler) staging his own breakdown, or whether it is in fact a traumatic collapse in front of an audience. Again, like the city it takes place in, the reading seems a movement between performed image and lived reality, coaxing one into the other until each are prickled with the other’s shadow.

‘Manichean visions revive disputed and despoiled London ground. Poetry in light and stone‘ – Iain Sinclair

Published : Animal Drums on Hotel Magazine and 3am April 22, 2020

A beautifully curated page of Animal Drums material on Hotel Magazine, with a small intro to the film, after its first screening at the whitechapel gallery, and a poem from the film, and Iain Sinclair’s poem responding to the film https://partisanhotel.co.uk/Animal-Drums

If you’re fortunate enough to have perceptive friends, whom, deep down, don’t wish you disappointment, then they’ll likely tell you, cautiously, what your work is about. Just as a good friend will tell you, you can’t keep a wild animal in a small London flat and then be surprised when it bites you.

My friend Camille Brooks has been a film projectionist in London cinemas for three decades. He’s seen a lot of films. He told me The Animal Drums is about the uncanny sensation of being in a part of London where you once were for the first time, and realising, in that moment of memory, not that things have changed, for London has never not changed, but whether actually it is the same place. These are different sensations. When you revisit your childhood home, yes, everything is smaller than you remember, and experiences, strangely of course, can lay themselves around you like tracing paper. But in London, to be by the grand union canal out past Willesden Junction, where I first was in the city over a decade ago, and where we shot so much of the film, is to arrive at a place that makes one feel as though one was never there at exactly the same moment of knowing you were.

The film is about development, sure, but not capital. It’s too ludic for that. It’s about people being squeezed, sure, but not because of greed. This is too much like a thing that everyone knows, even the greedy. The film is about the possibility of invisibility in the city. Can we still hide our weird behaviour? Our misdeeds and fetishes, and stupid hobbies like writing strange texts almost no one wants to read? It is about the beauty of a certain geographical space, so densely furrowed that it has no light left for the kind of “clarity” that produces righteousness, the pretence of entirely black and white thinking and morality, and no matter how much small clusters of human animals in London think they are on the ball, just one paper thin wall away, no one gives a shit about what they think or do.

My friend Gareth Evans said The Animal Drums is the first full length film poem he’s seen in the 21st century. He has a tendency to be too generous. But the film inevitably has a kind of abstract linguistic drive as its base. Josh Alexander and I were interested in whether film grammar is a metaphor or might be taken literally. And if it’s a poem somewhat, then it’s also a documentary, quite apparently and it’s also a narrative melodrama with found actors. It’s an attempt to use very specific technical tools, available only to the medium of film, with its manipulation of so many sensory elements, to generate something closer to what I take a poem to be.

Inevitably, watching the film for the first time on a cinema screen at Whitechapel Gallery, I realised it is about finding one’s own self-interest absurd, and how this is inescapable. That any turn to the outside will only reinforce the inside. That the harder the concrete, the softer the brain, the quick the chaos, the deeper the silence. The film pixelates my body, distorts my voice, sits me next to people I’ve met and breaks open our conversations into what they are. It evokes the small marginal shadows that seem so much more cavernous in the past and shows almost nothing in the slips of darkness. It watches wormwood scrubs, Kensal Green cemetery, new Whitechapel, an awkward performance, the India club, the catacombs of some city church you won’t know anyway. It can be such a despondent film, because it’s always sad and funny to realise how ridiculous one is. But it made me and a few other people laugh. This seems fitting, given its subject matter, that the experience of its own makers seeing it, was a slightly flat disturbance in an image no one was watching.

The film was also posted up on the 3am magazine lockdown Buzzwords series https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/3am-in-lockdown-41-joshua-alexander-steven-j-fowler

On the film at Oxford’s Ultimate Picture Palace : March 6, 2019

The first screening outside of London of my feature length poetry film made with Josh Alexander happened in Oxford, at the beautiful 100 year old one screen Ultimate Picture Palace. Josh is at Ruskin and the place was pleasingly busy. I again found it difficult to sit and watch, though I should have, but perhaps that is not the point of making a film, to watch it. The day itself, lolling in oxland and wandering around in the sun, was pleasant. To travel, to go and see your own film screened, it is a privilege not lost on me.

Maybe the coolest thing about this screening is the film had to be certified. It has been given a 12. You must be 12 years old to watch this film. No unaccompanied children. No U for me. No PG. No 15. No 18. 12 12 12.

We’re also screening before Green Book, so an oscar race ensues….

On the film at Whitechapel Gallery Cinema January 18, 2019

https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/events/joshua-alexander-steven-j-fowler-animal-drums/

It’s been a month since my first feature length film, made with (owed to) Joshua Alexander, was at Whitechapel Gallery Cinema. It was a strange night, satisfying, undoubtedly, but strange for me to experience sat the rear of the cinema, watching myself, my own film, on a huge screen. It was wonderful so many friends and people I don’t know came out, and the introduction by Iain Sinclair, where he firmly placed Josh and I in the tradition of Patrick Keillor et al, was pretty wonderful, as a moment of recognition. So the experience, as a night, was brilliant. And I feel the achievement of finishing a film is a thing to be left alone, to be enjoyed.

However it was all uncanny because in watching the film in this way, the first time removed from Josh and I and editing, in a sense, I saw what it was really about, as a piece of work. And this was different than what I thought it was about. It was a little disturbing, but perhaps that’s best. And really we owe this night, and the momentum it’s given the film, entirely to Gareth Evans, a constant hero of the often hidden work that needs working in London. He was so helpful to us and continues to be.

On/After ‘Animal Drums’ by David Spittle

An essay circling SJ Fowler & Joshua Alexander’s motion-picture-poem

Four years in the making, The Animal Drums is a collaboration between poet and artist SJ Fowler and moving image artist Joshua Alexander. The Animal Drums is a feature-length art-film exploring the sad, macabre, abstract threat of a contemporary London in the grips of constant and nefarious growth. The film charts the the particular, baffled and morbid character of English attitudes to mortality, along with the specific influence of place and conformity on the quintessentially English deferral of emotion and melodrama. It captures the ambiguous menace of an often accidentally humorous resolve, manner, apology and understatement so prevalent in the English character within a city that is proudly un-English, and it dwells upon the unfortunate consequence of blind development. Here, David Spittle offers an analysis of the neurosis of place—be it public or private; cultural or corporate—that sits at the centre of the city under Fowler and Alexander’s lens in Animal Drums to question ideas of form, function and communication considered over the course of its running time.

Animal Drums is the first feature-length film by poet Steve Fowler and filmmaker Joshua Alexander but, as the inhumanly low voiceover drawls nearing its end (but not in ending): ‘it is not a film, you wake and find yourself in pastures new.’ As much as ‘pastures new’ might suggest a hopeful Albion, something visionary clearing its throat inside the jangling attention of psychogeography… here, any moment of calm or release—the bees diligently knocking from leaf to leaf in a summer drone or a canal’s steady mirror—these are only ever brief possibilities, less present in their potential to be realised than in their vulnerability to ruin. You might wake up, but only through the glitch and bruise of a changing city, reeling in an unwell mind and propelled by a questioning of where art or the artist might fit into this quick neurosis of place.

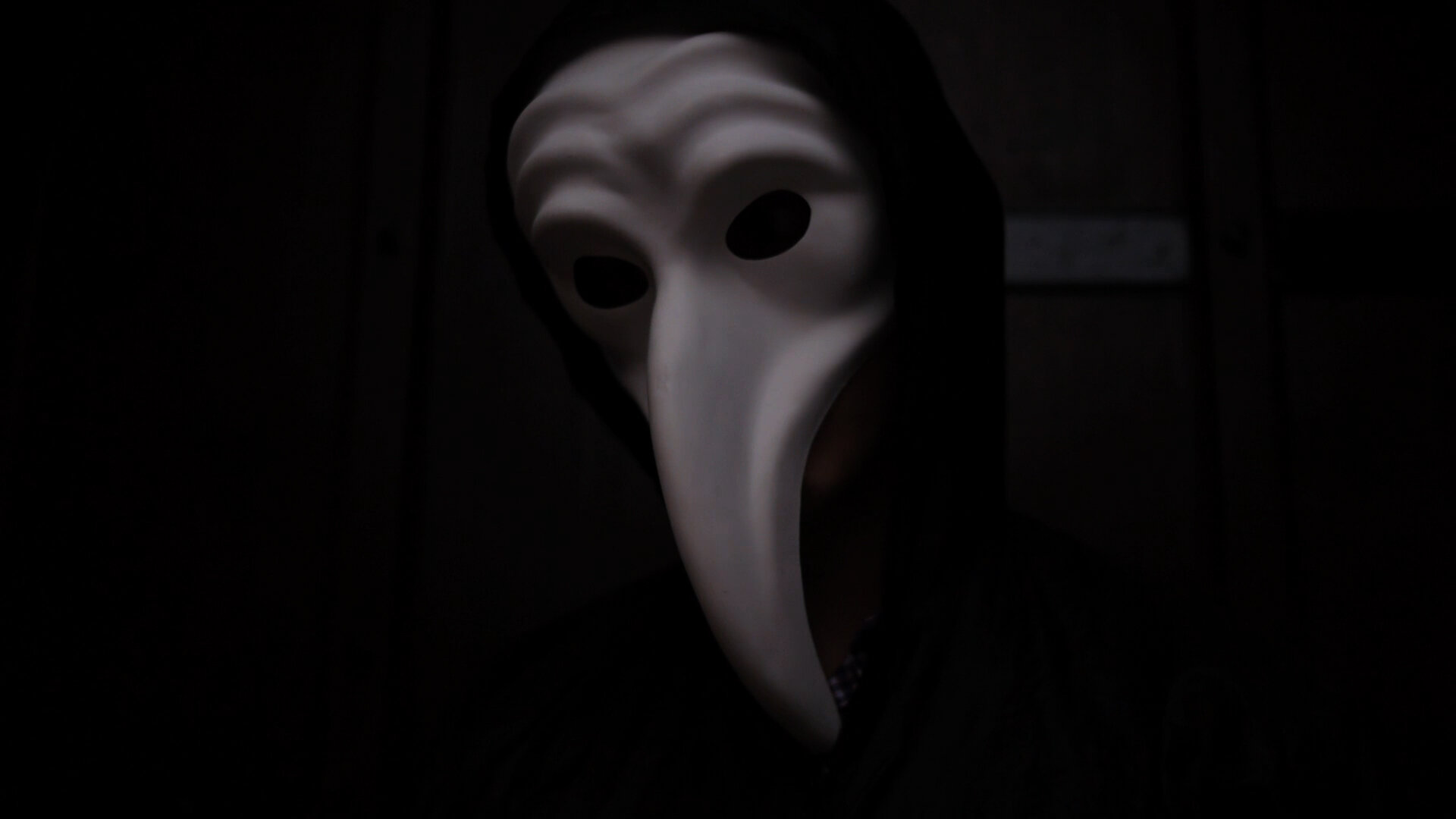

There is a plague doctor on a park bench, a man by the sea with his face censored, an ice-cream-van-man cheerily dishing out banality with conspiracy, rows of skulls, a teddy-bear mask locked into a furred rictus of performance art, a spectral economy that claims itself through ‘ghost flats’, the possibility that a painting was not a depiction of oyster-diving but drowning, and through it all the interrupted dialogue (real and imagined) of a man who is part of, but empoweringly and disturbingly apart from, the city around him. Primarily, this is a film that burrows into two itching sites of change, Steve Fowler (the persona, poetics, performance, and restless creation)… and London.

This a city with a cultural industry deployed to distract from its rapid property development and to sublimate the fall-out from escalating housing prices, a city that endorses inoffensive art as a way of virtue-signalling its way out of corrupt tax havens and the callous neglect of its populace. Endlessly promoting through cultural capital and tiresome heritage, the city advertises a pantomime of itself severed from both its art and local history. Pop-up Gyms compete with coldly lavish flats as partially exhumed versions of morality and memory stagger, pissed and forgotten, through disappearing space. Even the psychogeography of this perspective now seems to fold in on itself, approaching its own methods and tradition like another haunted territory. If Patrick Keiller’s film, London (1994), exchanged its wry detachment and stasis for an overwrought and pacing articulation of mental illness—one that just happened to find metaphorical release in the tolling bell of a housing crisis propped up by an absent rich elite and then tidily ‘artwashed’ by bland commissions, gathered like so many beige boxes ticked to appease a funded middle-brow born out of catering for corporate elevator music or for patronising a hypothetical ‘public’—this, Animal Drums, would be the necessarily unfinished result.

There is the distress, the offense, of breaking the surface with truly individual art (not prepared for, designed by, and explained to, committee), and there is also the breaking apart at/of what has become only surface. The film approaches this corporate management of self and city as simultaneously liberating in its realisation and appalling in its lived encounter: waking up to, and through, new experiences of anxiety. Each electronic pulse of sound and digital glitch of film becomes the ‘Animal Drum’: the actual bones sticking out from a synthetic skin of heritage and culture; or the crack in our glassy replication and distortion through online selfhood, tracing the sense of something no longer there. In a Lucifer-like red glow, Fowler (a nominal protagonist given a non-specific and slippery profile) confides, with a grinning intensity, ‘that is the thing about London, if it doesn’t go online I can kinda get away with anything’. Though online presence and the promotional ‘city’ of social media is never again explicitly mentioned, it is undeniably buzzing in the film’s agitated structure, informing the paranoia and interference it both addresses and becomes. Any virtual affirmation of self is the lonely volunteering for a self-surveillant template of living through the retreat from any actual living that then turns against itself (a self that was never more than advertising space and data) to decry that life has become a heightened experience of that same loneliness that compelled it into online expression.

Not unlike these tensions between the city and the self, both split by repressive economies of promotion and the snagging of lived actuality, this film includes its own disavowal: ‘this is not a film’. It is a phrase that announces as it denounces, not an unfamiliar paradox but one that is neither in the historically playful Surrealism of Magritte’s infamous, Ceci ne’st pas une pipe (1928-9), nor in the structuralist theorising taken up so keenly by the formalist work of the London Filmmaker’s Co-op (1966-1999, mostly active in the mid 70s). Animal Drums does not prioritise semiotic gestures of deconstruction but is instead wringing its trembling hands at the sad exhaustion of such thinking (the inevitable ‘always already’ disappointing in its false radicalism) or equivocating in the nervously excitable opportunity where one could ‘get away with anything’ but in realising such a chance is then intrusively hounded by contradiction and conflict.

As it ends, dismissing the possibility of any end in addition to its status as a film, Animal Drums could be imagined to loop back to its convulsive beginning: a pixilation of image accompanied by a distortion of sound. The bleeding of digital image into its bare and broken squared anatomies, like an error of early graphics wrestling with primitive thermal-imaging, it wretches at a kind of double-life and how it cannot help but split and double further. A film, a city and a self, as all and interchangeably caught between the destructive construction of any singular pretence at being and the fraught prospect of continuing to be, in and from, the rubble of that undoing.

The glitching pulp of red that begins the film keeps flashing across in other sequences, a blinked glimpse of the plague doctor and occasionally a peaceful but disintegrating shot of a forest. These images become like obsessive thoughts or the rupturing of flashbacks…it is half way through the film that we realise the incoherent red glitch is a distortion of a figure about to read, a performance. Steve Fowler has often looked at ways to unsettle, include or challenge audiences in order to resurrect the polite coma of most poetry readings into an unpredictable exchange between people. But it is that space, the reading—and more significantly, the performance—that seems to encapsulate a locus of anxiety for the film: a moment where the personal and persona of what might constitute Steve Fowler is allowed to blur and seem vulnerable. He mutters into the microphone, ‘It’s funny, people have all these thoughts in their mind and you speak to them…’ he trails off, repeats and trails back, as if lost and even afraid. This is followed by the admission, ‘I have a problem with impulse control’, which is then repeated around four times before descending into an apologetic mantra: ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry…’For the film, it is unclear whether this is the protagonist (that both is and isn’t Steve Fowler) staging his own breakdown, or whether it is in fact a traumatic collapse in front of an audience. Again, like the city it takes place in, the reading seems a movement between performed image and lived reality, coaxing one into the other until each are prickled with the other’s shadow.

This is a poet who, within just seven years has published nine poetry collections, two art books, a selection of fifteen collaborative and hard to categorise ‘other’ publications, had his own solo exhibition, conducted and curated a multitude of interviews with European poets (the Maintenent series with 3am Magazine), organised hundreds of events (mainly around the Enemies project) and whose art (in poetry/performance/the visual and audio) splits its energy between accident and intention to often explore an uncomfortable ambiguity between the offensive and its jagged critique or parody. The position or role of ‘offense’ is a potent drive behind much of Fowler’s fragmented questioning, as alive in his poetry as it is in the film. The problematic insistence on the ‘problematic’ in art has itself become increasingly problematic. The polarized bludgeoning of forces like Twitter have created a binary culture whereby the progressive and ongoing work to remove institutionalised prejudice and broaden inclusivity in art is damagingly conflated with a need to reductively limit art to moralising megaphones of ideology. Animal Drums splinters this conviction and instead opens up a troubling examination of where the troubled mind might go, anonymous and vulnerable or overlooked and dangerous, lonely or free, lost in a city equally beset by the drive to insist upon moralising cultural dedication at the very same time it deepens a perversion of those values. The plague doctor’s mask never slips but the film suggests that maybe the plague we are now confronted with is one of masks.

David Spittle has poetry published in Blackbox Manifold, 3am, The Literateur, Datableed, Zarf, and is translated into French by Black Herald Press. Twice shortlisted for the Melita Hume Prize (2015/2016) and included in the Best New British and Irish Poets 2016 Anthology (Eyewear Press). His first pamphlet, B O X, is with HVTN Press (September, 2018). In addition to poetry, he has written the libretti to three operas, performed at various venues around Cardiff and at Hammersmith Studios in London. In 2014 David was commissioned to write a song cycle for the Bergen National Opera, since performed internationally. He has curated a series of interviews, Light Glyphs, with poets-on-film and filmmakers-on-poetry. This ongoing series has included John Ashbery, Guy Maddin, Sophie Mayer, Andrew Kötting, Redell Olsen, John Adams, and Lisa Samuels. See here for Spittle’s website.